Episodes

Thursday Dec 07, 2017

December 7 National Union of Steam Engineers Founded

Thursday Dec 07, 2017

Thursday Dec 07, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1896.

That was the day eleven steam engineers met in Chicago to found the National Union of Steam Engineers, the forerunner of the International Union of Operating Engineers.

Ten of the eleven came from the stationary field. They often worked 60-90 hours a week in dangerous working conditions.

Constructing and operating steam boilers was highly skilled, labor-intensive and potentially deadly work.

At the time, steam powered railroad and construction shovels, hoists and cranes for high-rise construction and electric power generation.

Many flocked to San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake to help rebuild that city. Others left for Panama to work on the Canal.

By 1912, the union was issuing charters to locals that represented construction steam engineers and locals that represented fixed boiler operators.

It was renamed the International Union of Operating Engineers in 1928. During World War II and after, thousands worked as Navy Seabees, building military bases, airfields and roads.

The Federal Highway Trust Program opened up work for thousands more in the construction of the nation’s highway system.

Today, you can find Operating Engineers on bridge and dam projects, skyscrapers and pipelines. Its logo, the steam gauge was originally set at 80 psi but now points towards 420 psi.

Some think the change came as a result of operating high-pressure boilers for naval ships and steamboats. Others speculate the change came when the 600-psi gauge became the industrial standard.

The International Union of Operating Engineers administers one hundred apprenticeships in state of the art facilities, requiring 6000 hours of on the job training and 400 hours of classroom instruction.

It represents more than 400,000 members in 170 locals throughout the United States and Canada.

Wednesday Dec 06, 2017

December 6 Deadliest Day in Mining History

Wednesday Dec 06, 2017

Wednesday Dec 06, 2017

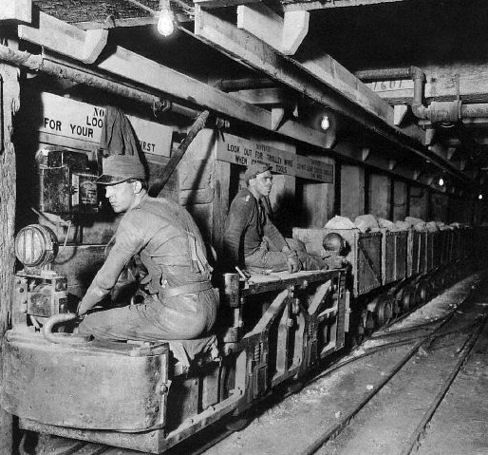

On this day in labor history, the year was 1907.

That was the day an explosion rocked Fairmont Coal Company’s number 6 and number 8 coal mines in Monongah, West Virginia, killing 367 miners.

Newspaper reports estimated the number of dead to be as high as 500. It is considered the worst mine disaster in the history of the United States.

Most miners were killed instantly as the explosion destroyed the mine entrance and its ventilation system.

Those not killed instantly suffocated from poisonous gas.

Earth tremors were felt eight miles away. The force of the explosion buckled pavement, collapsed buildings and derailed streetcars. More than 3200 miners had died in 1907.

With three more mine disasters before the end of the year, the last month became known as Black December. In January, a coroner’s jury verdict ruled that a blow out shot ignited coal dust and made number of recommendations for safer practices.

But David McAteer tells a different story in his history of the disaster.

He argues that the tipple had a design flaw that led to occasional coal car derailments as they exited the mine.

On this day, there had been a derailment with coal cars crashing to the bottom of the shaft and taking out the electrical and ventilation systems with it, igniting the coal dust in the process.

The disaster generated a surge in demands for greater mine safety, leading to the creation of the Bureau of Mines in 1910.

The Bureau could conduct research and safety training but was powerless to conduct inspections or safety enforcement.

Miners would continue to fight for the better part of the century for safety regulations and enforcement.

Tuesday Dec 05, 2017

December 5 Reviving the Sit Down Strike

Tuesday Dec 05, 2017

Tuesday Dec 05, 2017

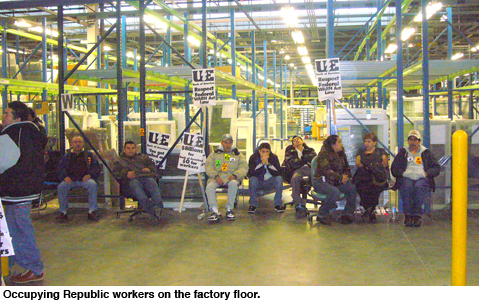

On this day in labor history, the year was 2008.

That was the day UE local 1110 members at Republic Windows in Chicago began a five–day occupation to protest the imminent closure of their plant.

A month earlier, Republic workers witnessed management moving machinery out of the factory.

They began monitoring where the machinery was going and soon learned it was headed for a new, non-union plant in Iowa.

They planned a possible plant occupation. By December 2, management announced the plant was closing in just three days.

Republic Windows owner Richard Gillman blamed Bank of America for refusing to extend credit, just as the federal government had bailed out the banks in a $700 billion deal.

Workers learned they would receive no severance or vacation pay, despite WARN Act mandates.

The next day they rallied out in front of Bank of America, chanting, “You got bailed out, we got sold out.” Workers were determined to occupy the plant that Friday, when they went to pick up their last paychecks.

Police refused to remove the sit-downers and the occupation quickly made national news.

Local labor leaders and trade unionists, activists and politicians all visited strikers and lent their support. Journalist Kari Lydersen recounts the events in her book, Revolt on Goose Island, noting the “donations of food, blankets, pillows, sleeping bags and other necessities that poured into the factory.”

Protests of Bank of America spread across the country. By the following Wednesday, workers learned that though they could not keep their plant open, they would at least win severance and vacation pay.

In 2012, some of those workers reopened the plant under the name, New Era Windows, as a worker-run cooperative. They specialize in energy efficient vinyl windows.

Monday Dec 04, 2017

December 4 Contempt of the Court

Monday Dec 04, 2017

Monday Dec 04, 2017

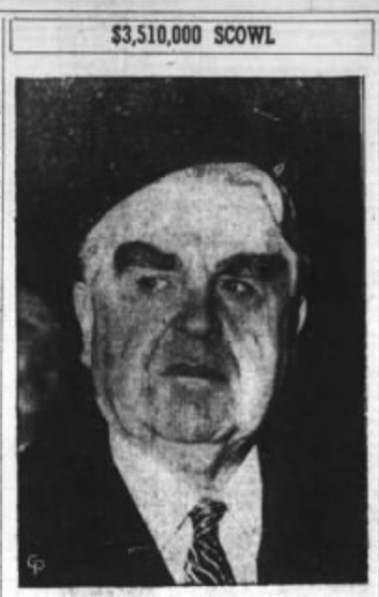

On this day in labor history, the year was 1946.

That was the day Federal Judge T. Alan Goldsborough fined John L. Lewis $10,000 and the United Mine Workers $3.5 million.

In what was characterized as “a roaring courtroom scene,” Lewis rose to challenge the judge to fine him whatever he wanted.

The judge had just found Lewis and the UMW in contempt of court for ignoring his November 18 order to head off a soft-coal strike, then in its fourteenth day.

Judge Goldsborough had replaced his order with a temporary injunction after the government demanded a judgment that the strike was illegal and must end.

Goldsborough ruled the strike was “an evil, demonic, monstrous thing that meant hunger and cold, unemployment and destitution--a threat to democratic government itself.”

He insisted he was a friend of labor, but that Lewis should be sent to prison.

UMW chief counsel, Welly K. Hopkins, snapped back defiantly, stating that the government was seeking to “break the union politically, financially and morally.”

The federal government had seized the mines in May and was now threatening to run them with Army engineers if Lewis didn’t order miners back to work.

AFL, CIO and Railway Brotherhoods all rallied to Lewis’ defense.

The Detroit labor movement vowed a 24-hour general strike in support. But by the 7th, Lewis retreated, ordering miners back to work until March 31st.

Facing the real threat of the Supreme Court action to uphold the $3.5 million fine, Lewis stated he wanted the Court to “be free from public pressure superinduced by the hysteria and frenzy of an economic crisis.”

Lewis and the UMW were tied up in appeals court for months while they attempted to negotiate new contract terms.

Sunday Dec 03, 2017

December 3 General Strike in Oakland

Sunday Dec 03, 2017

Sunday Dec 03, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1946. That was the day a general strike erupted in Oakland, California.

Workers, mostly women, had been on strike for a month at two downtown department stores.

Teamsters honored their picket lines and refused to make deliveries. Infuriated owners of Hastings and Kahn’s demanded their merchandise and turned to the city for help.

On this day, police assembled early in the morning to clear the streets of picketers. They attacked strikers, forced them off the streets and set up a perimeter of machine guns to escort scab delivery trucks through.

One striker recalled, “I was black and blue for six months from their clubs.” Outraged truck drivers, bus drivers and streetcar operators all stopped, got out of their vehicles and joined the strikers, quickly filling downtown Oakland.

By the end of the day, the city was completely shut down. 142 AFL unions called for a labor holiday in support of the strikers and now 130,000 workers were on strike in solidarity.

UAW member Stan Weir recalled that it was the bus drivers, many just returned from the war, who led the strike. The streets that night had a carnival like atmosphere. War vets led a march to City Hall to demand the resignation of the Mayor and the City Council for their attempts to break the strike.

The general strike quickly forced the administration to stop the scabhearding. But local labor leaders were divided over what some considered a near insurrection and called the strike off 54 hours later.

The retail workers were left to fight on their own for another five months. But for a few days, workers got a taste of their own power.

Saturday Dec 02, 2017

December 2 John Brown Hanged

Saturday Dec 02, 2017

Saturday Dec 02, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1859.

That was the day John Brown was hanged in Charles Town, Virginia in what is now West Virginia.

He had been sentenced to death on charges of treason, murder and insurrection for his role in the raid on the United States Federal Armory at Harper’s Ferry.

Brown and twenty-one abolitionists intended to seize the arsenal there, then build a free settlement in the Appalachian Mountains.

From there, abolitionists and free people of color would wage a guerrilla war against the slave labor system throughout the South.

Convicted on November 2, Brown resisted plans for rescue and prepared to die a martyr.

On this day, John Brown wrote his last statement: “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed, it might be done.”

He was marched out of the Jefferson County Jail through a crowd of onlookers that included Stonewall Jackson and John Wilkes Booth to the gallows, where he was hanged.

While many abolitionists distanced themselves from his actions, they defended him and memorialized him after his death.

Fredrick Douglass remarked many years later, “His zeal in the cause of my race was far greater than mine-it was as the burning sun to my taper light-mine was bounded by time, his stretched away to the boundless shores of eternity. I could live for the slave, but he could die for him.”

Friday Dec 01, 2017

December 1 Exploitation in the Mines

Friday Dec 01, 2017

Friday Dec 01, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1912. That was the day the Anaconda Copper Company instituted its rustling card system at its copper mines in Butte, Montana. The company used the rustling card in two ways: as a work permit and as way to keep track of miners. A miner looking for work would first have to apply for a card. Miners had to present information about citizenship status, English literacy skills, work history and two years of employer references. Once the card was approved, the miner would then be allowed to apply for work. The Butte Miners’ Union charged it was the company’s way of blacklisting those who had quit, been fired or known as a union militant. By 1917, the Metal Mine Workers Union and the IWW added that the company was looking to “nip agitation in the bud.” They alleged employers were holding on to cards or denying them altogether for no reason. According to historian Paul Brissenden, both unions maintained the company was looking “to punish those who were at one time active in the socialist administration of Butte Mayor Lewis J. Duncan, to prevent the Socialist Party from again securing a foothold in Butte, to strengthen the hands of the more conservative unions and to curb the industrial unionism of the IWW and Metal Mine Workers Union.” The company asserted its right to keep its enemies out of the mines, alleging they presented a danger to mine safety. But the unions shot back, stating the blacklist meant the hiring of untrained, inexperienced workers who presented the real danger. Brissenden notes that many union radicals continued to work in the mines despite the card system.

Thursday Nov 30, 2017

November 30 Mother Jones passes at 100

Thursday Nov 30, 2017

Thursday Nov 30, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1930. That was the day the world lost the miners’ angel, Mother Jones. She had crossed the country many times over, been involved in practically every strike that built the labor movement; stood with miners and steel workers and mill children everywhere. Mother Jones had asked to be buried with the Virden Martyrs, killed in the Massacre of 1898, at Union Miners Cemetery in Mt. Olive, Illinois. Dozens of labor leaders including AFL president William Green, attended her funeral in Maryland, where she had been living. Then, AFL representatives, several Illinois miners and others boarded the Baltimore and Ohio train to accompany her body to Mt. Olive. Historian Dale Fetherling describes the scene as her body arrived. A band played “Nearer, My God, To Thee” as onlookers bowed their heads and wept. Survivors of the Virden Riot bore the casket to the Odd Fellows’ Hall where it lay in state… The town of 3,500 with its strong and violent heritage, was thronged by thousands of coal diggers.” At least 15,000 turned out for the funeral, broadcast on WCFL, the Chicago Federation of Labor’s radio station. The labor priest, Reverend John Maguire gave the memorial address and officiated at the funeral in Mt. Olive’s Roman Catholic Church of the Ascension. He asked: “What weapons had she to fight the fight against oppression of working men? Only a great and burning conviction that oppression must end. Only an eloquent and flaming tongue that won men to her cause. Only a mother’s heart torn by the suffering of the poor. Only a towering courage that made her carry on in the face of insuperable odds. Only a consuming love for the poor.”

Wednesday Nov 29, 2017

November 29 A Deadly Dust in the Air

Wednesday Nov 29, 2017

Wednesday Nov 29, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1937. That was the day the National Labor Relations Board began hearings on an unfair labor practice brought by the International Union Mine, Mill and Smelters. Mine, Mill had been fighting the union busting tactics at Eagle-Picher Lead Company. The union had been organizing lead and zinc miners in the Tri-State area of Kansas, Missouri and Oklahoma. During the Great Depression, they built the union by emphasizing safer working conditions, stressing the hazards of silicosis and tuberculosis. In their book, Deadly Dust: Silicosis and the Politics of Occupational Disease, Gerald Markowitz and David Rosmer note that one of Mine Mill’s demands included the elimination of the company clinic. They argued it was used to target and fire diseased workers, rather than provide a safe work environment. Mine Mill also organized other area industries, to counteract the near total power of the mine owners in the region. When the union called a strike at area mines in May 1935, the area’s largest producer, Eagle Picher Lead moved quickly to force a lockout and establish a company union. During the hearings, the union was limited in its ability to raise health and safety issues. They did win reinstatement and back pay for workers fired during the strike. But the case brought national attention to silicosis in the Tri-State area. In a letter to Francis Perkins the following year, the head of the Cherokee County Central Labor Body hoped to secure legislation to compel the companies to install ventilation systems and safety devices. He noted the average life of a miner was 7-10 years, with many dying in 2 or 3 years. But a federal standard on silica was still decades away.

Tuesday Nov 28, 2017

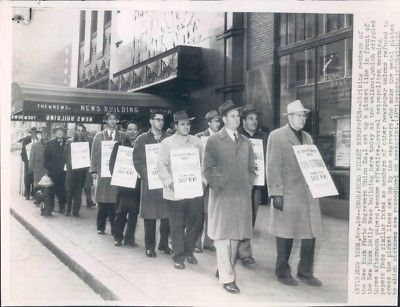

November 28 Stop the Presses Workers Demand Decent Wage

Tuesday Nov 28, 2017

Tuesday Nov 28, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1953. That was the day 400 photo-engravers at six New York City newspapers walked off the job. Members of the AFL’s International Photo-Engravers Union had just voted down arbitration. All but one local newspaper, The New York Herald Tribune were idled as 20,000 newspaper workers refused to cross the engravers picket lines. Six days into the strike, that newspaper suspended operations as well. Writers at The New Yorker magazine remarked they were “curled up with the Wall Street Journal, The Daily Worker and a two-day old copy of La Prense.” In the decades before digital images, photoengraving was a labor-intensive process. Highly skilled workers made metal plates from which newspaper images were printed. Photo-Engravers had been working without a contract since the end of October. They demanded a $15 a week raise. The Newspapers Association was only willing to grant $3.75. The other newspaper unions had been offered similar wage and benefit packages, far below their demands. They knew that whatever they won or lost depended on the victory of the Photo-Engravers strike. So they walked out in solidarity. Federal mediators intervened in an attempt to settle the strike. Hysteric newspaper editors across the country shrieked that the union had accomplished what the government would never dare to do: subvert the freedom of the press! They sulked that the strike had broken 35 years of industrial harmony and peace; adding that the ungrateful workers didn’t appreciate just how good they had it. After eleven days, members voted to end the walkout and let a fact-finding board solve the dispute. Three months later, that board upheld the Newspaper’s Association original offer of $3.75 a week plus benefits.