Episodes

6 hours ago

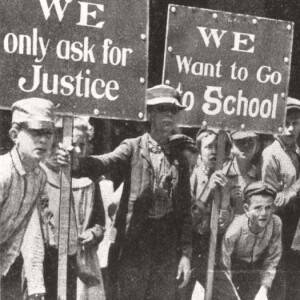

June 17 - March of the Mill Children

6 hours ago

6 hours ago

On this day in Labor History the year was 1903. Mary Harris better known as “Mother” Jones held a rally in Philadelphia.

The famous Irish-American labor leader had come to Pennsylvania to support a strike of textile workers. As many as one-hundred thousand workers were out on strike.

2 days ago

June 16 - Bankrupt

2 days ago

2 days ago

On this day in Labor History Pinkerton Detectives arrived at job sites across the US to escort workers off the premises. No--this was not at a railroad or coal mine in labor’s distant past. It was at the offices of what was once the largest computer seller in the United States. And the year was 2000.

2 days ago

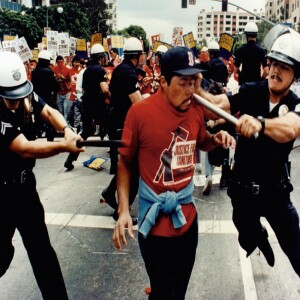

June 15 - Justice for Janitors

2 days ago

2 days ago

On this day in Labor History the year was 1990. About 400 janitors were protesting at Century City, a large office complex in Los Angeles.

It was part of SEIU’s Justice for Janitors campaign in LA. The janitors had gone out on strike against International Service Systems.

4 days ago

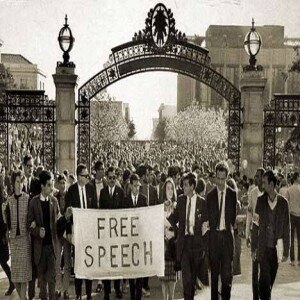

June 14 - The Fight for Free Speech

4 days ago

4 days ago

On this day in Labor History the year was 1924. Three-hundred members of the International Workers of the World, or Wobblies, gathered at their union hall in San Pedro California. They were holding a benefit for two of their members who had been killed in a railway accident. For the past year, the KKK had targeted the San Pedro IWW members.

5 days ago

June 9 - Gay? You’re Fired

5 days ago

5 days ago

On this day in Labor History the year was 1991. That was the day that a San Francisco man, Jeffrey Collins, received $5.3 million for wrongful termination from Shell Oil. The judge ruled the company had fired Jeffrey because they found out he was gay.

6 days ago

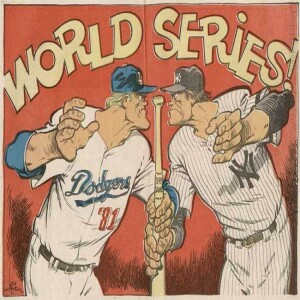

June 12 - Team Owners Attack Free Agency

6 days ago

6 days ago

In 1981 the Los Angeles Dodgers dropped the first two games of the World Series to their rivals, the New York Yankees. The Dodgers would come roaring back, sweeping the next four games. And so closed the curtain on one of the strangest seasons in baseball history.

7 days ago

June 11 - The Banana Massacre

7 days ago

7 days ago

On this day in Labor History the year was 1913. Police in New Orleans shot at maritime workers striking against the United Fruit Company.

Two workers were wounded. A third laid dead in the street. At the time of the strike the port in New Orleans was one of the busiest U.S. ports for importing bananas.

Tuesday Jun 10, 2025

June 10 - The Equal Pay Act of 1963

Tuesday Jun 10, 2025

Tuesday Jun 10, 2025

On this day in Labor History the year was 1963. That was the day President John F. Kennedy signed the Equal Pay Act.

The goal of the act was to end wage discrimination against women.

Monday Jun 09, 2025

June 9 - Birth of a Fighter

Monday Jun 09, 2025

Monday Jun 09, 2025

On this day in Labor History the year was 1865. Labor leader Helen Marot was born to a wealthy Quaker family in Philadelphia.

Helen grew up around the written word, as her father was a book binder and seller

Sunday Jun 08, 2025

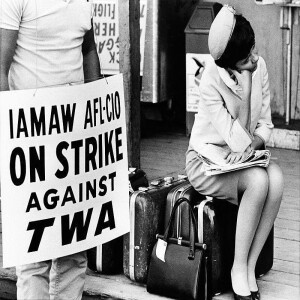

June 8 - The Silent Skies

Sunday Jun 08, 2025

Sunday Jun 08, 2025

On this day in Labor History the year was 1966. That was the day that the roaring of the jet age grew quiet across the United States.

35,000 members of the International Association of Mechanics went out on strike.