Episodes

Tuesday Nov 07, 2023

November 7 - Eisenhower Wields Taft-Hartley

Tuesday Nov 07, 2023

Tuesday Nov 07, 2023

On this day in Labor History the year was 1959.

That was the day that the US Supreme Court handed down a decision that would be a blow to the cause of labor.

Striving for the kind of major gains they had won in 1956.

The half a million members of United Steelworkers of America once again went out on strike.

The steel industry was extremely profitable and the workers demanded to share in the fruits of their labor.

Management wanted the ability to introduce new technology and policies to cut hours and employees.

The strike wore on for more than 100 days.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower ordered the steelworkers back to the plants.

He argued that the Taft-Hartley act gave him the legal means to issue the order.

A decade earlier Congress passed the Taft-Hartley Act over President Harry Truman’s veto as a way to curtail union rights.

The Steelworkers protested the constitutionality of the law, all the way to the Supreme Court.

The union lost.

In making its decision, the court referenced President Eisenhower’s explanation of the impact of the strike. “The strike has closed 85 percent of the nation's steel mills, shutting off practically all new supplies of steel. Over 500,000 steel workers and about 200,000 workers in related industries, together with their families, have been deprived of their usual means of support. Present steel supplies are low, and the resumption of full-scale production will require some weeks. If production is not quickly resumed, severe effects upon the economy will endanger the economic health of the nation."

The next January, the union and management signed a new contract.

The workers received a 7 cents an hour raise, a new automatic cost-of-living adjustment, improvements to their pension and health care benefits, job protections against proposed automation.

Monday Nov 06, 2023

November 6 - The Fight for Equality

Monday Nov 06, 2023

Monday Nov 06, 2023

On this day in Labor History the year was 1982.

That was the day that eleven women graduated from the New York City Fire Academy.

They were the first women firefighters ever to serve in the city of New York since the department was founded in 1865.

The inclusion of women firefighters did not come easily to New York.

In 1977 for the first-time women were allowed to apply to be firefighters.

Although many women had passed the written part of the exam they were continually denied employment because all failed the physical test.

The women sued citing discrimination.

One of the leaders of the suit was applicant Brenda Berman.

The Federal District Court in Brooklyn sided with the women.

Not everyone was happy about the decision.

A group of demonstrators came to City Hall before the graduation, with signs reading “I want to be save by Firemen.”

The Uniformed Firefighters Association challenged the ruling.

They tried to block the ceremony in the courts, arguing that training requirement had been changed to accommodate the women.

Despite the legal challenges the ceremony went on as scheduled.

In his speech Mayor Ed Koch said, “As all of us have known all along, bravery and valor know no sex.”

After the graduation, the controversy over women firefighters continued.

The women often faced sexual harassment on the job, and vilification on the editorial pages of city newspapers.

Bumper stickers reading “Don’t send a girl to do a man’s job” could be seen on the car bumpers of many male firefighters and at the city firehouses.

The women firefighters stood up to the harassment, testifying before the City Council and holding street demonstrations to bring awareness to their plight.

Monday Nov 06, 2023

November 5 - The Everett Massacre

Monday Nov 06, 2023

Monday Nov 06, 2023

On this day in Labor History the year was 1916.

That was the day when what came to be known as the On this day in Labor History the year was 1916.

That was the day when what came to be known as the Everett Massacre took place in Washington State.

The Everett Shingle Workers Union had gone out on strike in May.

Organizers from the Industrial Workers of the World came to the area to support the strike and to make a stand for free speech.

Over the summer tensions began to mount.

The police began to arrest IWW speech makers.

Then, in August, violence erupted between strike breakers and picketers at the Jamison Mill.

The IWW decided to bring in a group of about 300 members for free speech rally.

They came from Seattle by two steamer boats.

But the first boat was met at the docks by the sheriff and a large group of armed deputies.

A gun battle broke out.

One passenger, Ernest Nordstrom told the harrowing tale of what happened to the Seattle Union Record saying, “I couldn’t swear to where the first shot came from, but as it comes to me I thought the first shot was a warning shot not to go ashore. After that there were shots—gee whiz—all kinds of shots, and when they commenced all ran to the other side and the boat began to tip.”

“I am sure there is no excuse for this whatsoever-there need have been no bloodshed.”

The passenger avoided capsizing the boat, and turned around to flee back to Seattle.

At least five IWW members on board were killed, along with two of the deputies.

After the violence, the Shingle Workers union called off their strike.

74 IWW members were arrested, but only one stood trial. None were convicted.

“I am sure there is no excuse for this whatsoever-there need have been no bloodshed.” took place in Washington State.

The Everett Shingle Workers Union had gone out on strike in May.

Organizers from the Industrial Workers of the World came to the area to support the strike and to make a stand for free speech.

Over the summer tensions began to mount.

The police began to arrest IWW speech makers.

Then, in August, violence erupted between strike breakers and picketers at the Jamison Mill.

The IWW decided to bring in a group of about 300 members for free speech rally.

They came from Seattle by two steamer boats.

But the first boat was met at the docks by the sheriff and a large group of armed deputies.

A gun battle broke out.

One passenger, Ernest Nordstrom told the harrowing tale of what happened to the Seattle Union Record saying, “I couldn’t swear to where the first shot came from, but as it comes to me I thought the first shot was a warning shot not to go ashore. After that there were shots—gee whiz—all kinds of shots, and when they commenced all ran to the other side and the boat began to tip.”

“I am sure there is no excuse for this whatsoever-there need have been no bloodshed.”

The passenger avoided capsizing the boat, and turned around to flee back to Seattle.

At least five IWW members on board were killed, along with two of the deputies.

After the violence, the Shingle Workers union called off their strike.

74 IWW members were arrested, but only one stood trial. None were convicted.

“I am sure there is no excuse for this whatsoever-there need have been no bloodshed.”

Saturday Nov 04, 2023

November 4 - Will Rogers is Born

Saturday Nov 04, 2023

Saturday Nov 04, 2023

On this day in Labor History the year was 1879.

That was the day that Will Rogers was born in Oologah, Indian Territory, in what later became Oklahoma.

Rogers grew up on a ranch, and by 10thgrade had dropped out of school to be a cowboy.

Skilled with a lasso, he became a cowboy entertainer first in vaudeville then in silent film.

Rogers also had a syndicated column and a radio show where he became a popular political commentator.

With quick wit and humor Rogers helped to shape public opinion.

He brought humor to serious issues in a way later echoed by the likes of John Stewart and Stephen Colbert.

Rogers often talked about the plight of the American worker.

In 1931 he was asked to give a radio address for President Herbert Hoover’s Organization on Unemployment.

Rogers expressed the urgency of the unemployment that was sweeping the nation during the Great Depression.

He said, “The only problem that confronts this country today is at least 7,000,000 people are out of work.

That’s our only problem. There is no other one before us at all. It's to see that every man that wants to is able to work, is allowed to find a place to go to work, and also to arrange some way of getting a more equal distribution of the wealth in country…So here we are in a country with more wheat and more corn and more money in the bank, more cotton, more everything in the world—there’s not a product that you can name that we haven't got more of it than any other country ever had on the face of the earth—and yet we’ve got people starving.”

Saturday Nov 04, 2023

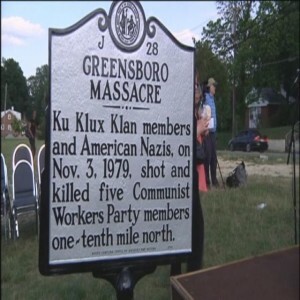

November 3 - The Greensboro Massacre

Saturday Nov 04, 2023

Saturday Nov 04, 2023

On this day in Labor History the year was 1979.

That was the day that became known as the Greensboro massacre.

Members of the Ku Klux Klan and American Nazi party shot and killed five participants in a demonstration held by the Workers Viewpoint Organization, later called the Communist Workers Party.

Workers Viewpoint organizers had come to Greensboro in an effort to strengthen the unions at the Cone Mills textile plants.

At the time, Cone Mills was the largest producer of denim in the world.

African American millworkers faced discrimination and dangerous conditions, including breathing in textile dust that was known to potentially cause brown lung disease.

Tensions between the communist organizers and the Ku Klux Klan began to mount.

Disagreements also arose between the communists and other union organizing efforts in Greensboro.

The Workers Viewpoint group decided to hold a “Smash the Klan” demonstration.

They coordinated the route of the march with the local police.

But on that fateful day no police were there to provide protection.

In broad daylight cars filled with Klansmen and Nazi members drove up and opened fire on the demonstrators.

Five people fell dead.

A criminal trial was held in 1980, and a federal Civil Rights trial took place in 1984.

Both times the defendants were acquitted by all-white juries.

In 2004, Greensboro began a “Truth and Reconciliation Commission” to address their community history.

The second chapter of the final report, recounts how Milano Caudle, the Nazi who owned one of the vehicles driven that day, later bragged in an interview “that the Klan “destroyed the damn union” with its actions against the marchers.”

After the tragedy, there was a strong backlash in the press against the communist organizers.

Thursday Nov 02, 2023

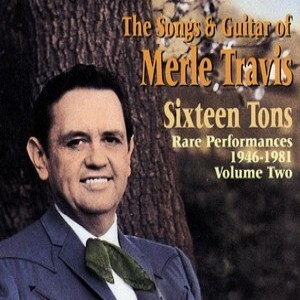

November 2 - Sixteen Tons

Thursday Nov 02, 2023

Thursday Nov 02, 2023

On this day in Labor History the year was 1955.

That was the day that the song “Sixteen Tons” first made an appearance on the Billboard country music chart.

It would reach the top spot and stay there for ten weeks.

Sixteen Tons told the story of the hard lives faced by coal miners.

The song talks about falling into debt at the “company store” a reality faced by many coal mining families.

The song had first been recorded by Merle Travis in the mid 1940s.

The song borrowed lyrics from things that Merle heard from his father, who was a coal miner.

Merle Travis sung the songs of working people.

He was labeled a Red and Communist, and during that era many stations would not play his music.

Sixteen Tons was recorded again by “Tennessee” Ernest Jennings Ford in 1955.

“Tennessee” Ernie’s grandfather and uncle had both worked in the mines.

Tennessee began to perform Sixteen Tons to enthusiastic crowds.

He then recorded it as a B side to his single “You Don’t Have to Be a Baby to Cry” for Capitol Records.

But the B side recording became the hit.

The song was so popular, it jumped off the country charts, and took the pop music number one spot for eight weeks and became a Gold Record.

Since then Sixteen Tons has been covered by a variety of artists from Johnny Cash to Tom Jones and Tom Morrello to ZZ Top and has become a true labor standard.

Wednesday Nov 01, 2023

November 1 - The Deadly Consequences of Scabbing

Wednesday Nov 01, 2023

Wednesday Nov 01, 2023

On this day in Labor History the year was 1918.

That was the day that bringing in a scab driver to run an elevated train in Brooklyn, New York ended in tragedy.

Members of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers were out on strike against the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Co..

The company had fired several union members for wearing union pins.

To keep the trains moving, the company hired replacements and put them to work with little preparation.

Edward Luciano received far less than the 60 hours of training that operators typically received before he made his fateful run.

The next day the New York Times reported on the deadly results.

A Brighton Beach Train of the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company, made up five wooden cars of the oldest type in use, which was speeding with a rush hour crowd to make up lost time on its way from Park Row to Coney Island, jumped the track shortly before 7 o-clock last evening on a sharp curve approaching the tunnel at Malbone Street, in Brooklyn, and plunged into a concrete partition between the north and south bound tracks.”

At least 93 people died.

Some estimates were more than 100 were killed.

The operator and several company officials were put on trial for manslaughter.

No one was found guilty.

The company did however pay out damages to some families.

Negotiations between the company and the union would continue until 1920.

The union eventually won most its demands.

In the years after the crash new safety measures were implemented for elevated trains to help guard against human error.

Tuesday Oct 31, 2023

October 31 - Happy Union Made Halloween

Tuesday Oct 31, 2023

Tuesday Oct 31, 2023

On this day in Labor History ghosts and goblins are going door to door to gather up candy. But did you know that some of that candy is made by union workers?

In Hershey, Pennsylvania, tagged the Sweetest place on earth you’ll find the nation’s chocolate center.

It wasn’t always so sweet for workers who in 1937 tried to win union recognition.

Then the company laid off some of the union organizers, and claimed it was due to seasonal cutbacks.

Outraged, 600 workers began a sit-down strike in the plant.

Local dairy farmers relied on Hershey to purchase their milk.

They grew increasingly angry at the strikers.

They joined with workers not participating in the strike, and other community members.

The angry mob stormed the plant to oust the strikers.

Twenty-five strikers were severely beaten and the sit-in strike ended.

But the next year, the Hershey workers tried again to form a union.

This time they affiliated with the Bakery and Confectionery Workers' International Union of America and established Local 464.

They are not the only union members who help make Halloween sweet.

Today the Bakery, Confectionary, Tobacco and Grain Millers Union Local 1 in Chicago, Illinois makes tootsie rolls.

If your candy of choice is Clark Bars or Thin Mints, you might want to thank a member of Local 348 in Cambridge Massachusetts.

And Local 125 makes Ghirardelli Chocolate in San Francisco.

Unfortunately things are not always so sweet. In September of 2016, 400 union workers at the Just Born candy factory in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania went out on strike. The company decided to change their pensions to 401ks for new hires and reduce health care contributions.

They make such iconic candies as Peeps, Mike & Ike’s, and Hot Tamales.

One strike slogan rang out “no pensions, no peeps!”

Monday Oct 30, 2023

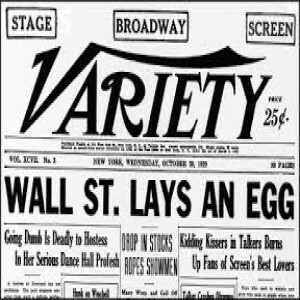

October 30 - Wall St. Lays an Egg

Monday Oct 30, 2023

Monday Oct 30, 2023

On this day in Labor History the year was 1929.

On that Wednesday morning, people across the United States woke up to newspaper headlines informing them that something had gone horribly wrong on Wall Street the day before.

Black Tuesday, as the day came to be known had capped off a devastating drop in the market that had begun with the Great Crash the prior Thursday.

Twenty-five billion dollars was lost in the crash, which would be about three hundred billion in today’s money.

The crash helped spark the Great Depression that saw unemployment soared to twenty-five percent and nearly half of the banks in the United States fail.

But the day after the crash, the news reports were not all doom and gloom.

While Variety declared in big, bold letters “Wall St. Lays an Egg” others headlines struck a different tone.

The New York Times wordyheadline stated “Stocks collapse in 16,410,030-Share Day; But rally at close cheers brokers; bankers optimistic to continue aid.”

The Chicago Tribune went with the more concise “Stock Slump Ends in Rally.”

Newspaper reporters attempted to explain the crash.

The Denver Post blamed the downturn on “gamblers,” the Philadelphia Evening Ledger blamed “the propagandists of gloom and economic terror” and the New York Times blamed “the reckless Wall Street speculators.”

But many papers also attempted to quell panic over the badnews from New York.

The Kansas City Star assured readers “once the adjustment is completed, the country will move forward to newlevels of prosperity.”

The Nashville Banner similarly predicted “The reaction had to come, and the country will be betteroff for the lesson it has had, costly though it be.”

That costly lesson became a devastating global depression.

Sunday Oct 29, 2023

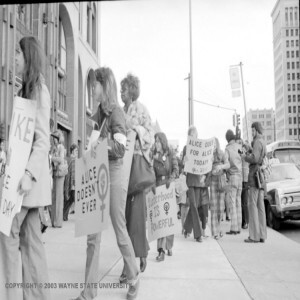

October 29 - Alice Doesn’t Day

Sunday Oct 29, 2023

Sunday Oct 29, 2023

On this day in Labor History the year was 1975.

That was the day that the National Organization for Women, or NOW, called for a strike by women across the nation.

They called the action, “Alice Doesn’t Day.”

This referred to a critically acclaimed movie by director Martin Scorsese that came out the year before, entitled “Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore.”

The main character in the film is Alice Hyatte, who pursues her dream of being a singer after she is widowed.

It was lauded by feminists as a story of women’s empowerment.

NOW used the film title, and asked women to participate with the slogan “Alice doesn’t...you fill in the blank.”

Women were encouraged to participate in the day however they could, including refraining from volunteering, shopping, and if possible working for one day to demonstrate their importance to the economy.

Women who could not skip work, were asked to wear arm bands to show their solidarity with the cause.

In an interview published in the Chicago Tribune, NOW President Karen DeCrow explained, “There is a myth that women in the work force could go home, but if they did our economy would stop. If all the secretaries did not come to work, all things would stop.”

But not all women were excited about the day.

Some anti-feminist women decided to protest the day by wearing pink, baking cookies and performing other stereotypical female tasks.

While NOW called the event a success, Time magazine deemed it “spectacular failure.”

One critique was that the event reflected the white, middle class dominance of the women’s movement.

Working class women, and especially women of color, had a much more difficult time withholding their labor.