Episodes

Sunday Oct 08, 2017

October 8 Locked Out and Ready to Fight

Sunday Oct 08, 2017

Sunday Oct 08, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1933.

That was the day garment factory owners locked out dressmakers in several shops throughout Los Angeles.

The women garment workers, overwhelmingly Mexican, had been organizing with the ILGWU for over a month.

They began conducting strikes at selected shops the previous month to press their demands.

The women wanted union recognition, a thirty-five hour workweek, an end to homework, shop floor committees, a guaranteed wage and more.

Historian Douglas Monroy observes that their demands reflected the harsh working conditions they faced.

It was a volatile, competitive, seasonal industry.

Businesses worked tirelessly to undercut each other and job out the work.

Women workers were routinely unemployed or underemployed, subject to widespread wage theft and discrimination.

They were frustrated by promises of the new National Industrial Recovery Act, which promised the right to organize but held no provisions for enforcement.

Employers flaunted the new legislation and continued to discharge workers for union activity.

When the employers forced a lockout, Local 96 looked to the AFL’s Central Labor Council to sanction a general dressmakers strike, which started four days later on October 12.

As many as 3,000 Latina strikers maintained solid picket lines, despite dozens of arrests.

ILGWU organizer Rose Pesotta arrived from New York to help with food distribution and packing the picket lines.

The rank and file leadership produced a bilingual strike bulletin and made daily radio announcements.

The strike ended in arbitration that conceded few gains to the garment workers.

But the women of Local 96 continued to organize throughout the Los Angeles area.

They led a series of strikes that finally won the closed shop in 1936.

Saturday Oct 07, 2017

October 7 Joseph Labadie Dies

Saturday Oct 07, 2017

Saturday Oct 07, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1933.

That was the day Detroit anarchist labor leader, Joseph Labadie died.

Born in Paw Paw in 1850, Jo was born to descendants of French immigrants and grew up among Native Potawatomi peoples in southwest Michigan.

He became a printer, joined the local Typographical Union No.18 and worked for the Detroit Post and Tribune.

He was an early leader of the Socialist Labor Party.

By 1878, Jo organized the first Knights of Labor Assembly in Detroit.

He served as the first president of the Detroit Trades Council and founded the Michigan Federation of Labor.

He wrote tirelessly for a number of labor and socialist newspapers across the country.

He embraced anarchism and soon produced a popular column titled, “Cranky Notions.”

Labadie enjoyed the company and correspondence with radical labor leaders like Emma Goldman, Albert and Lucy Parsons, Eugene V. Debs, Benjamin Tucker, Terrance Powderly and others of the Progressive Era.

He was often referred to as ‘The Gentle Anarchist’ for his insistence on non-violence and distancing from those Anarchists who advocated the use of violence as an acceptable tactic.

Labadie was also known to never throw out any printed material relevant to labor or radical causes.

His biographer, Carlotta Anderson notes that, “the story of his life, deeds and thoughts is abundantly revealed through the treasure trove of letters, periodicals, clippings, manuscripts, booklets, photos and circulars once stored in his attic and now housed in the Labadie Collection of the University of Michigan. His stockpile of documents of social protest has proved a boon to scholars, enabling them to study the early labor movement in detail.”

When he died at the age of 83, he considered this to be his legacy.

Friday Oct 06, 2017

October 6 Fannie Lou Hamer is Born

Friday Oct 06, 2017

Friday Oct 06, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1917.

That was the day Civil Rights leader Fannie Lou Hamer was born in Montgomery County, Mississippi.

She was the youngest of 20 children.

Her parents were sharecroppers and she began working the fields at the age of six.

At the age of 12, Fannie had to drop out of school to sharecrop to meet the needs of her family.

Marrying in 1944, she and her husband continued to work as sharecroppers on a plantation near Ruleville.

After decades of abject poverty and Southern political repression, Fannie Lou Hamer joined up with voter registration activists in 1962.

When she and seventeen others traveled to Indianola to register, Fannie was fired from her job and driven from the plantation she had worked at for decades.

She began working with the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee and played a central role in organizing Freedom Summer.

In a short time, Fannie was repeatedly arrested, beaten and shot at for her activism.

She suffered kidney damage after police beat her nearly to death in a Winona, Mississippi jail as she traveled home from a literacy workshop.

By 1964, she helped to found the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, which challenged the all-white delegation to the Democratic Convention.

President Lyndon Johnson was so threatened by live testimony she was giving before the Convention’s Credentials Committee, that he orchestrated an emergency press conference to preempt the broadcast.

When the Committee attempted a backroom deal to seat just two MFDP delegates with no voting rights at the convention, Hamer and other delegates left in disgust.

Hamer continued her activism but her life was tragically cut short in 1977 from hypertension and breast cancer.

She was just 59.

Thursday Oct 05, 2017

October 5 Labor Candidates Step Up

Thursday Oct 05, 2017

Thursday Oct 05, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1886.

That was the day Henry George accepted the nomination to run for mayor of New York on the United Labor Party ticket.

In cities across the country, trade unionists met to found state labor parties and to hammer out political platforms for local and state elections.

In New York City, ULP advocates issued the Clarendon Hall platform and nominated Henry George as the ULP candidate for the mayoral race.

George had gained prominence with the 1879 publishing of his book, Progress & Poverty.

In it, he addressed private land ownership as the basis for inequality and advocated for a single tax system.

At New York’s Cooper Union that evening, where thousands of supporters gathered, George addressed the crowd.

He presented the ULP platform: higher pay, shorter hours, better working conditions, government ownership of railroads and communications and an end to police repression.

Burrows and Wallace describe the scene that night in their book, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898.

During his speech, George declared that, “this government of New York City—our whole political system is rotten to the core.”

He argued that “politicians had made a trade out of assembling votes and selling them to powerful interests; what business got in return was police protection, lax enforcement of housing and health codes, friendly judges and fat franchises. To purify the political order, working class voters had to sever ties to all the established parties and choose from their own ranks.”

For a party that had just been founded weeks before, George came in second.

But like its sister organization in Chicago, the New York ULP would split over the issue of socialism within a year.

Tuesday Oct 03, 2017

October 3 The Father-Son Strike

Tuesday Oct 03, 2017

Tuesday Oct 03, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1932.

That was the day the State Militia was called into Kincaid, Illinois.

164 high school students had just walked out of the classroom, declaring themselves on strike.

They were protesting the school board’s use of coal from the Peabody Coal Company.

The students walked out in solidarity with their fathers, who were on strike against the Peabody Coal mine in nearby Langleyville over wage concessions.

The father-son strike, as it was referred to, was one more in a series of protest actions that came on the heels of the founding of the Progressive Miners of America a month earlier.

Thousands of Illinois miners had just voted with their feet to repudiate John L. Lewis’ UMWA over wage concessions.

After their founding conference, new PMA leaders began aggressively organizing non-union mines.

They marched into mining towns and ordered non-union diggers out of the mines.

They also struck UMW mines, picketing against the industry standard of $5 a day that had been set by the latest concessionary contract.

At some mines, the PMA was able to win the old $6.10 a day wage.

Throughout the month, the State National Guard had been called out to a number of mining towns to quell armed conflicts between PMA and UMW supporters.

The Peabody Coal mine at Langleyville had been shut down for months by ongoing PMA/UMW conflict.

Now it had reopened under heavy National Guard protection and was the only mine operating in Christian County.

The striking fathers were PMA miners picketing the continued mine operations under the UMW concessionary contract.

The years-long Illinois mine wars had just begun.

Monday Oct 02, 2017

October 2 Striking for a Future

Monday Oct 02, 2017

Monday Oct 02, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1949.

That was the day Americans awoke to fears the nationwide steel strike would spread rapidly to include key fabrication plants.

Half a million steel workers had joined 400,000 coal miners on strike the morning before.

The miners’ resolve to defend their $100-a month pensions, instituting what John L. Lewis called the “no-day work week,” emboldened the steel workers to walk out of the mills.

Within 24 hours, 96% of all steel production in the country was completely shut down.

USW contracts were due to expire on the 15th, But the writing was on the wall.

The mill owners decried anything close to mine pensions as nothing short of socialistic and refused to budge in negotiations.

USW president Phil Murray thundered that those companies that failed to agree to demands for non-contributory pensions and insurance would be shut down.

But militants warned that President Truman’s Fact-Finding Board had already watered down strike demands.

The President’s Board had been established to put off two previous strike deadlines.

The ‘guidelines’ it issued only encouraged steel magnates to stand tough against USW demands.

These included a 30-cent raise plus increased company insurance and pension contributions.

Now it had become a defensive struggle over whether steel workers would have to begin contributing to health and pension plans through wage cuts.

By the time steelworkers ended their strike forty-two days later, they had won the $100 a month pension, minus what they would receive from social security.

And they had to begin contributing to a health insurance plan with no wage increase at all.

Still, workers celebrated that they had successfully defended the USW against the all out union-busting drive.

Sunday Sep 17, 2017

September 17 The “Southern Differential”

Sunday Sep 17, 2017

Sunday Sep 17, 2017

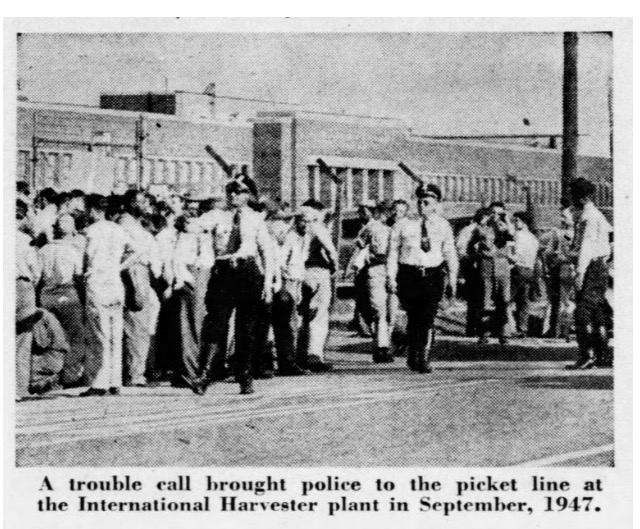

On this day in labor history, the year was 1947.

That was the day workers at the International Harvester plant in Louisville, Kentucky had had enough.

They had just rejected a pay scale lower than that of Harvester workers elsewhere.

In her recent article for Leo Weekly, historian Toni Gilpin refers to the lower pay as the “Southern Differential.”

Harvester workers walked off the job in a 40-day strike.

Black and white Louisville workers were united in a rare form of solidarity.

International Harvester had had a long labor-hating history.

Its forerunner had been the McCormick Reaper Works, the site that sparked the 1886 Haymarket incident in Chicago.

Harvester had been able to keep the unions out until the Farm Equipment Workers/CIO finally organized there in 1941.

And the FE followed Harvester as they attempted to escape to the union-free South.

The FE successfully organized the new Louisville plant, just two months before the strike.

Workers learned quickly that they were paid much less making the same equipment as their brothers in Chicago, Indianapolis and elsewhere.

Gilpin adds that FE literature forthrightly stated, “Once the Negro and white workers were united, the low-wage system of the South would collapse.”

Workers pressed for their demands, and appealed to area farmers for support.

They stressed that farmers would not pay less for equipment, simply because local workers were paid less.

Black and white workers picketed together, ate together and planned their strike together at their new union hall.

Harvester initially tried to redbait FE leaders.

When that failed, the company was forced to grant steep wage increases.

Gilpin cites FE News, which reported “two smashing victories in hand, one over International Harvester, the other over the Mason-Dixon, low-wage line.”

Saturday Sep 16, 2017

September 16 Demanding 52 for 40

Saturday Sep 16, 2017

Saturday Sep 16, 2017

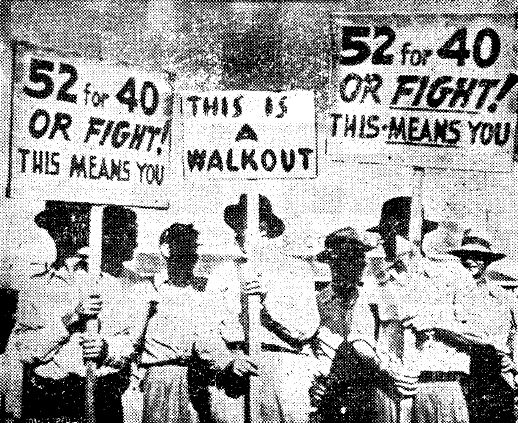

On this day in labor history, the year was 1945.

That was the day oil workers walked off the job.

The strike soon spread to 20 states and involved more than 43,000 workers at 22 oil companies.

After years of wartime wage freezes, the union’s demand was 52 for 40—fifty-two hours pay for 40 hours work.

Workers demanded a 30% pay increase, shift differentials and an eventual return to the 36-hour workweek.

The strike began in Michigan at the Socony-Vacuum refinery in Trenton.

From there it spread to Gulf, Sinclair and Shell.

By October 4, President Truman signed executive order 9639, allowing the Secretary of the Navy to seize petroleum operations.

The Oil Workers International Union/CIO immediately called off the strike and ordered its members back to work.

A month later, the Navy had still not relinquished control of operations.

The union considered Truman’s seizure a betrayal.

There was no mechanism put in place to settle the dispute or consider workers demands.

By January 1946, the Oil Panel, created by the Secretary of Labor, finally awarded oil workers an 18% wage increase.

Though disappointed, the union considered it a victory.

They asserted the strike action was significant on a number of levels.

The first nationwide industry strike had just forced the oil companies to meet with the union for the first time.

The OWI believed the groundwork for industry-wide bargaining had finally been established.

It had been the first post-war strike and had forced the government to begin moving away from wartime wage controls.

Of the post-war strikes, it won the largest pay increase.

And importantly, it broke the power of Standard Oil to dictate wages to the industry through its dealings with its “independent union.”

Friday Sep 15, 2017

September 15 350,000 GM Workers Strike

Friday Sep 15, 2017

Friday Sep 15, 2017

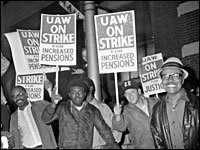

On this day in labor history, the year was 1970.

That was the day 350,000 GM workers kicked off a 67-day strike.

It was the largest auto strike since the end of World War II.

According to historian Jefferson Cowie, it was likely the costliest.

In his book, Stayin’ Alive, Cowie notes that the strike cost GM a billion dollars in profits and nearly bankrupted the union.

But he adds it “lacked the proletarian drama that fired journalists’ hearts.”

For Cowie, it was an example of labor-management cooperation, “a civilized affair.”

But historian Jeremy Brecher points out that The Wall Street Journal drew different conclusions about the strike at the time.

In a series of articles, the paper noted that labor-management cooperation during the strike served ironically, to get workers back to work.

A long and costly strike served a number of functions.

It wore down strikers’ expectations.

After eight or ten weeks, workers would be amenable to terms they initially rejected.

It also provided an escape valve for built up frustration over working conditions.

And a long strike served to coalesce internal union factions around a common enemy, strengthening the union’s leadership in the process.

For management, a long and costly strike leant hope that workers would be reluctant to strike in the future.

But Brecher notes, these ideas about workers motives nearly backfired.

Strikers simply wouldn’t budge on their demands.

They made gains in wages, pensions and cost of living allowances.

And they were finally able to retire after 30 years.

But critics argued the agreement fell short of initial demands.

And workers lacked more say in the workplace.

This would be a key issue in the many strikes and wildcats in the years to come.

Thursday Sep 14, 2017

September 14 General Strike in Illinois

Thursday Sep 14, 2017

Thursday Sep 14, 2017

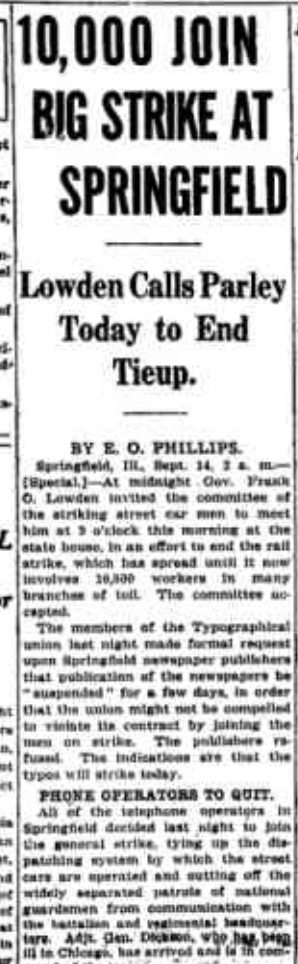

On this day in labor history, the year was 1917.

That was the day Illinois Governor Frank Lowden hoped to meet with striking streetcar men in an effort to end their strike.

Transit workers in Springfield, the state’s capitol, had been off the job since July 25th.

But the strike had gained so much support that Springfield had now erupted into a full blown general strike.

According to the Sangamon County Historical Society, thousands of “union members shut down mines, railroads, bakeries, restaurants, laundries and construction sites… following the violent crackdown of a pro-labor march by state police and militia.”

That march had been scheduled for September 9.

The unions hoped to show support for the striking streetcar men after a number of clashes between strikers and state militia.

After they were denied a permit, many of the 50 or so unions decided to march anyway, and were attacked.

Some were shot, more than 40 suffered bayonet-inflicted injuries.

By the 11th, most everyone in Springfield had walked off the job.

Striking women shoe factory workers stopped a streetcar, pulling the scab drivers off by force.

By the end of the week, as many as 12,000 members of 34 unions in the city were on strike.

When telephone operators walked off the job, they paralyzed communications of the scab streetcar drivers and the State National Guardsmen.

The streetcar strikers refused to meet with the governor until troops were withdrawn from the city.

The governor insisted disloyal, pro-German forces were at fault for the “labor troubles.”

By the 16th, the streetcar men agreed to negotiate and the general strike was called off.

But the company refused to meet striker demands for recognition and higher wages or even to take them back.