Episodes

Tuesday Nov 14, 2017

November 14 OSHA publishes its Lead standard

Tuesday Nov 14, 2017

Tuesday Nov 14, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1978.

That was the day OSHA published its lead standard.

The standard reduced permissible exposure by 75% to protect nearly a million workers from damage to nervous, urinary and reproductive systems.

As early as 1908, Alice Hamilton, the mother of occupational medicine, noted that lead had endangered workers as far back as “the first half-century after Christ.”

In their book, Deceit and Denial: The Deadly Politics of Industrial Pollution, historians Gerald Markowitz and David Rosner add that “throughout her distinguished career, Hamilton was deeply involved in uncovering the relationship between lead and disease in the American workforce.”

Hamilton’s groundbreaking research on the effects of lead paved the way for a growing uproar against its continued use.

After the Occupational Safety and Health Act passed in 1970, occupational and public health activists pushed hard for a lead standard.

A new generation of industrial hygienists emphasized how unsound, industry-driven conclusions regarding “safe lead levels” impacted women workers and workers of color.

Industry had long asserted that women and African-Americans were simply more susceptible to lead poison, which served to justify discrimination in hiring.

Some unions accepted these terms, if only to demand a stringent lead standard that included immediate implementation of engineering controls.

But leading hygienists like Jeanne Stellman blasted these arguments.

Stellman insisted such conclusions reflected racial and gender bias rather than any credible scientific evidence.

She added that men, women and children, regardless of race or ethnicity, were all adversely affected by lead exposure.

The final standard adopted was considered a compromise.

Discrimination in hiring has continued and enforcement proves difficult.

But even a watered-down standard was too much for the lead industry.

They have been fighting it ever since.

Monday Nov 13, 2017

November 13 A Workplace Safety Hero Dies in Suspicious Crash

Monday Nov 13, 2017

Monday Nov 13, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1974.

That was the day Karen Silkwood was killed in a mysterious car crash.

Though her death was ruled a one car accident, some maintain she was forced off the road.

Silkwood was a union activist and representative for Local 5-283 of the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers.

She worked at Kerr McGee’s Cimarron plutonium plant in Crescent, Oklahoma, making plutonium pellets for nuclear reactor fuel rods.

Meryl Streep popularized her life in the 1983 film, Silkwood.

Karen’s union loyalty only grew after the company crushed a strike in 1972.

She was elected to the union bargaining committee just as the company moved to force a decertification election.

She also served as a union health and safety rep.

Silkwood found a number of apparent violations: routine contamination exposure, faulty respiratory equipment, falsified inspection records, and improper storage of radioactive material.

She met with OCAW leader, Tony Mazzocchi to highlight safety issues in a campaign to beat back decertification.

It worked.

Then Karen testified before the Atomic Energy Commission, worried about her own contamination.

It was clear her home was contaminated too.

She worked tirelessly to gather the documentation and the evidence, detailing the company’s life-threatening negligence.

And on this day, Karen Silkwood was headed to Oklahoma City to meet Mazzocchi’s assistant, Steve Wodka and a New York Times reporter to present evidence she collected.

She never made it.

Her car was found with rear end damage, near skid marks, in a ditch along Route 74.

While the company attempted to smear her as a drug addicted lesbian who deliberately contaminated herself, they would eventually settle with her family for nearly $1.4 million.

Karen Silkwood became a model and a hero for women workers and all those who fight for safe workplaces.

Sunday Nov 12, 2017

November 12 Ellis Island Closes Forever

Sunday Nov 12, 2017

Sunday Nov 12, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1954.

That was the day Ellis Island closed its doors.

More than 12 million immigrants had passed through its gates since its opening in 1892.

Those steerage and third-class passengers coming to America were processed at the island between 1892 and 1924.

They were routinely subject to medical inspections to determine they were free of disease.

Legal inspections included questions regarding birth, occupation, destination, finances and criminal record.

Its busiest year was 1907 with more than a million arriving to enter the United States.

During World War I, the Island was used as a detention center for presumed enemies and those considered foreign-born subversives.

After Congress passed the restrictive Immigration Act of 1924, arrivals entering the country slowed to a trickle.

Then Ellis Island became primarily a detention and deportation center.

During World War II, thousands of Germans, Italians and Japanese made up the majority of those detained, awaiting deportation.

It also served as a military hospital for returning servicemen and training center for the Coast Guard.

By 1950, Ellis Island served as a holding center for arriving Communists and Fascists, who were prevented entrance under the recently passed Internal Security Act.

A Norwegian seaman who had overstayed his leave was released the day the Island closed and told to catch the next ship back to Norway.

In 1965, President Johnson made Ellis Island part of the National Park Service.

A massive restoration of the Island began in 1984, organized by Lee Iacocca’s Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation.

It reopened as the Ellis Island Immigration Museum in 1990, featuring numerous exhibits, publicly accessible immigration records and the award-winning film documentary, “Island of Hope, Island of Tears.”

Saturday Oct 14, 2017

October 14 A Day of Protest in Canada

Saturday Oct 14, 2017

Saturday Oct 14, 2017

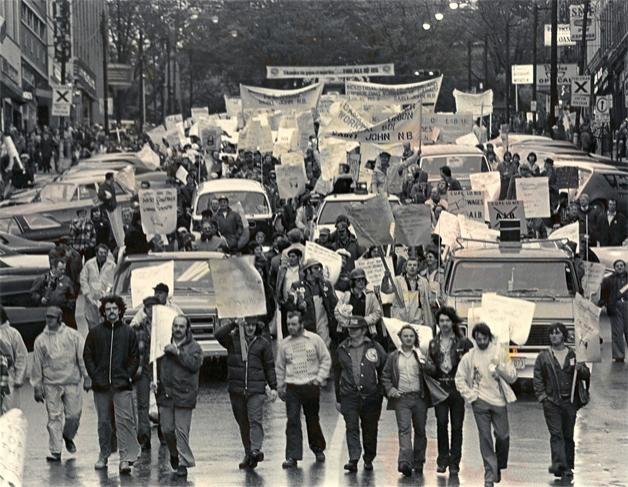

On this day in labor history, the year was 1976.

That was the day more than a million Canadian workers walked off the job in a Day of Protest.

The Canadian Labour Congress called the general strike.

Workers downed their tools against a three-year wage controls plan implemented by then Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau.

Trudeau had actually campaigned against wage controls during the 1974 elections.

A year later, the Liberal government introduced the C-73 Anti-Inflation Bill.

It was considered the worst attack on labor since the 1930s, when bargaining rights were first legalized.

Trudeau’s wage controls suspended collective bargaining rights for all workers and amounted to deep wage cuts.

Public sector workers were hit hardest as many hospital, school and municipal workers teetered on the edge of desperation from already low wages made worse.

But for a day at least, many industries across Canada came to a screeching halt.

Forestry, mining and auto production all completely shut down.

Many towns and cities were one hundred percent on strike, even among the non-union workforce.

Saint John in New Brunswick, Sudbury, Ontario, Sept Iles, Quebec and Thompson in Manitoba were all cities where the strike was most successful.

But elsewhere, the strike was uneven.

Many public sector workers stayed on the job, while in cities like Vancouver, pickets successfully shut down bus service and newspaper deliveries.

Most heralded the Day of Protest as a fierce show of power against a years’ worth of wage controls.

But others argued that a one-day action was not enough.

To combat the attacks on labor, any general strike would have to keep the country shut down until the program of wage controls was finally defeated.

Friday Oct 13, 2017

October 13 An International Rescue Effort

Friday Oct 13, 2017

Friday Oct 13, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 2010.

That was the day thirty-three Chilean miners were finally pulled to safety after being trapped for sixty-nine days.

Workers had been mining copper and gold twenty three hundred feet down, at the San Jose mine near the northern city of Copiapo, when the mine caved in, in early August.

The Compania Minera San Esteban Primera waited several hours to notify authorities and rescue efforts only began two days later.

Trapped miners initially tried to escape through ventilation shafts but found required ladders missing.

Each route they attempted was blocked by fallen rock or threatened additional collapse.

A state owned mining y took over rescue efforts and soon they began, as Geologist Sorena Sorensen noted, prospecting for people.

Initial exploratory boreholes failed to locate miners because mineshaft maps had never been updated.

Rescuers had no idea whether miners were even still alive.

Finally, seventeen days later, the eighth borehole reached them.

The miners tapped on the drill and taped notes to it, alerting rescuers above they were indeed alive and well.

Food, medicine and other supplies were lowered down to them as rescue efforts intensified.

Mini cameras were also lowered down and the miners videotaped messages of their continued ordeal.

They told how they continued to search for possible escape routes and agreed to ration their limited food supplies so they could all survive.

The first of three drilling plans to free the miners began.

It was an international effort.

The Chilean Navy consulted with NASA to design and construct the rescue pods.

Throughout the entire process, rescuers worked to prevent additional cave-ins and rock falls.

Finally the extraction process began and in less than 48 hours all emerged as heroes.

Thursday Oct 12, 2017

October 12 A Unionized Resting Place

Thursday Oct 12, 2017

Thursday Oct 12, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1899.

That was the day union miners in Mt. Olive, Illinois began commemorating Miners Day.

Every year thousands came into town for a parade, music and speeches.

Mt. Olive was the site of the only union-owned cemetery in the United States, established by UMWA local 728, in the aftermath of the Virden massacre.

A year before to the day, striking miners had been killed in a shoot out with company guards attempting to herd scabs into the mines in Virden, Illinois.

But, as Mother Jones’ biographer, Eliot Gorn notes, the “train never unloaded its cargo and the company was forced to settle.”

The union hoped to erect a gravesite monument commemorating those miners who had been killed at Virden.

But they were refused by those who considered the fallen miners to be murderers, not martyrs.

That’s when the UMW established the Union Miners Cemetery.

On this day, nearly 10,000 turned out for the union’s memorial ceremony.

The UMW unveiled a monument dedicated to fallen Virden miners, E.W. Smith, Joe Gitterle, Ernst Kaemmerer and E.F. Long.

The day was filled with parades, music, laying of wreaths and speeches.

Haymarket widow and radical activist, Lucy Parsons was among the speakers.

In his book Death and Dying in the Working Class, Michael Rosenow notes that her presence drew a direct connection between the fallen miners and the Haymarket martyrs, cut down while advancing the cause of labor.

Thousands traveled to Mt. Olive every year for celebrations, including Eugene Debs, miners’ leader John Mitchell and Mother Jones.

In 1923, Mother Jones asked to be buried with her boys, noting “they are responsible for Illinois being the best organized labor state in America.”

Wednesday Oct 11, 2017

October 11 The Woman Behind the Lens Passes On

Wednesday Oct 11, 2017

Wednesday Oct 11, 2017

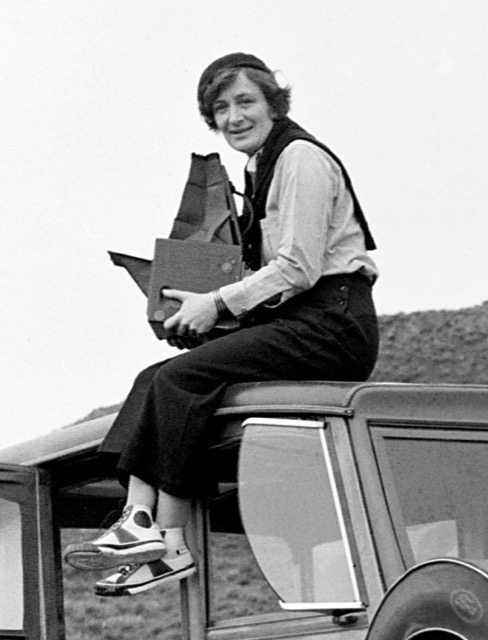

On this day in labor history, the year was 1965.

That was the day acclaimed photojournalist Dorothea Lange died.

She is celebrated for her work documenting the Great Depression for the Farm Security Bureau.

Lange’s photos captured images of migrant workers, sharecroppers and the rural poor.

Her iconic photo, Migrant Mother, is probably her most well known image.

It depicts a despondent, Dust Bowl mother surrounded by her hungry children.

Lange was born in Hoboken, New Jersey in 1895.

She suffered the effects of polio as a child, which left her with a permanent limp.

She studied photography at Columbia University in New York, and eventually settled in the Bay Area.

When the Great Depression hit, she began photographing labor strikes, breadlines and soup kitchens, the homeless and unemployed.

The Resettlement Administration hired her soon after.

Nowadays, we can access images from around the world at a moment’s notice that broaden our understanding of current events.

But until the 1930s, few Americans could access media that adequately depicted the desperate social conditions engulfing the nation.

Federal programs that funded projects like Lange’s brought Depression-era images into the public eye.

Americans soon realized their suffering wasn’t caused by personal failure; that millions across the country were experiencing destitution brought on by broader economic forces.

During World War II, Lange worked for the War Relocation Authority, where she documented forced evacuation and internment of Japanese-Americans.

Her images, especially of Manzanar, were withheld from the public until after the war and were accessible to the public through the National Archives.

After the war, she taught at San Francisco’s Art Institute and cofounded the magazine Aperture.

She has been heralded as an innovator and has influenced generations of documentary photography.

Tuesday Oct 10, 2017

October 10 Mill Workers Strike

Tuesday Oct 10, 2017

Tuesday Oct 10, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1912.

That was the day mill workers began to walk off the job at the Phoenix and Gilbert Knitting Mills in Little Falls, New York.

The strike was sandwiched between the Bread and Roses strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts and the 1913 Paterson textile strike.

American, Hungarian, Polish and Italian workers, over 70% of them women, struck against wage reductions.

Their hours had just been cut from 60 hours a week to 54, and their wages adjusted accordingly.

A recent factory inspection commission investigation revealed deplorable working and living conditions, among the worst in the state.

As a result, state legislators passed protective legislation restricting women’s work hours.

Many social reformers pushed for laws like these in the hopes of improving women’s quality of life by minimizing their exploitation on the job.

But the reduction in hours spelled disaster for these mill women, who then faced a loss of income that ranged from 75 cents to $2 a week.

Socialists in nearby Schenectady, including the socialist mayor George Lunn, arrived in town and were promptly arrested for giving open-air speeches in support of the strikers.

IWW organizers soon followed to help organize picketing, daily strike parades and strike committees at each of the factories.

They quickly established IWW Local 801, National Industrial Union of Textile Workers.

By the end of the month, mounted police closed in on the women strikers and began clubbing them, many into unconsciousness.

The police raided strike headquarters and arrested IWW strike committee leaders.

But the women strikers stood strong and were celebrating victory by the beginning of the year.

They won full reinstatement and 60 hours pay for 54 hours work.

Monday Oct 09, 2017

October 9 Mary Ann Shadd Cary is Born

Monday Oct 09, 2017

Monday Oct 09, 2017

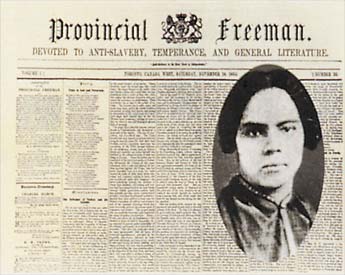

On this day in labor history, the year was 1823.

That was the day abolitionist and women’s suffragist, Mary Ann Shadd Cary was born.

Her parents were free blacks of color in the slave state of Delaware.

They were involved with many prominent abolitionists and active in the Underground Railroad.

The family moved to Pennsylvania, where Mary and her siblings were educated in Quaker schools.

As a young woman, Mary became a teacher and returned to Wilmington, Delaware where she opened a school for black children.

Once the Fugitive Slave Law was passed in 1850, Mary and many other free blacks fled to Canada to safely continue their abolitionist work.

She opened a school for fugitive slaves in Windsor, Ontario just across the river from Detroit.

Mary soon came under fire in the local press for insisting the school be racially integrated.

She responded by starting her own newspaper, The Provincial Freeman.

She and her husband, Thomas often traveled to the United States to continue their anti-slavery work.

They were present at John Brown’s 1858 Constitutional Convention.

Mary worked with Osborne Perry Anderson to publish his 1861 memoir, A Voice from Harper’s Ferry.

Anderson had participated in Brown’s raid and was the lone African-American survivor.

After her husband’s death, Mary returned to the United States with her children to help recruit black soldiers to the Union Army.

Once the Civil War was over, Mary moved to Washington D.C to teach.

She enrolled in Howard University where she earned a law degree.

There she joined the National Woman Suffrage Association and worked with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony.

She continued to advocate for civil rights and women’s equality until her death in 1893.

Sunday Oct 08, 2017

October 8 Locked Out and Ready to Fight

Sunday Oct 08, 2017

Sunday Oct 08, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1933.

That was the day garment factory owners locked out dressmakers in several shops throughout Los Angeles.

The women garment workers, overwhelmingly Mexican, had been organizing with the ILGWU for over a month.

They began conducting strikes at selected shops the previous month to press their demands.

The women wanted union recognition, a thirty-five hour workweek, an end to homework, shop floor committees, a guaranteed wage and more.

Historian Douglas Monroy observes that their demands reflected the harsh working conditions they faced.

It was a volatile, competitive, seasonal industry.

Businesses worked tirelessly to undercut each other and job out the work.

Women workers were routinely unemployed or underemployed, subject to widespread wage theft and discrimination.

They were frustrated by promises of the new National Industrial Recovery Act, which promised the right to organize but held no provisions for enforcement.

Employers flaunted the new legislation and continued to discharge workers for union activity.

When the employers forced a lockout, Local 96 looked to the AFL’s Central Labor Council to sanction a general dressmakers strike, which started four days later on October 12.

As many as 3,000 Latina strikers maintained solid picket lines, despite dozens of arrests.

ILGWU organizer Rose Pesotta arrived from New York to help with food distribution and packing the picket lines.

The rank and file leadership produced a bilingual strike bulletin and made daily radio announcements.

The strike ended in arbitration that conceded few gains to the garment workers.

But the women of Local 96 continued to organize throughout the Los Angeles area.

They led a series of strikes that finally won the closed shop in 1936.