Episodes

Saturday Jan 08, 2022

January 8

Saturday Jan 08, 2022

Saturday Jan 08, 2022

Often significant days in history pass with little attention. Today in labor history, January 8, 1811, is one such day. On that day Charles Deslonde, an enslaved sugar laborer in the New Orleans territory led what became one of the largest slave revolts in American history.

Friday Jan 07, 2022

January 7

Friday Jan 07, 2022

Friday Jan 07, 2022

Today in labor history, January 7, 1919 began what is known as Semana Trágica, or Tragic Week in Argentina. Labor unrest had been mounting in Buenos Aries. On January 7, police killed four workers who were striking for better conditions at an ironworks plant.

Thursday Jan 06, 2022

January 6

Thursday Jan 06, 2022

Thursday Jan 06, 2022

Today in labor history, January 6, 1878, is the birthday of renowned Illinois poet Carl Sandburg. He was born to Swedish immigrants in Galesburg, Illinois. Later Sandburg worked as an editorial writer at the Chicago Daily News. He was part of a group of poets and novelists, known as the “Chicago Literary Renaissance.” Sandburg became most well-known for his poetry, which won two Pulitzer Prizes. He also won a third Pulitzer for his biography of his hero Abraham Lincoln. Sandburg’s poems often evoked images and explored themes of the industrialized United States. This was especially true of his 1920 volume, Smoke and Steel. In this collection Sandburg wrote about workers in Gary, Indiana and farmers around Omaha, Nebraska. He wrote about railroad workers and steel workers. His words instilled unexpected beauty in these industrial scenes. Sandburg wrote in free verse, a style that did not rhyme. He used accessible language in his poems, making them available to the “common man.” He would take short tours around the U.S. reading his poems and playing folk songs on guitar. His poems gained a wide, popular readership. The opening lines of his poem “Chicago,” so captured the workers and spirit of the city, these words remain indelibly entwined in the city’s image: “Hog Butcher for the World, Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat, Player with Railroads and the Nation's Freight Handler; Stormy, husky, brawling, City of the Big Shoulders.”

Wednesday Jan 05, 2022

January 5

Wednesday Jan 05, 2022

Wednesday Jan 05, 2022

Today in labor history, January 5, 1914 the Ford Motor Company raised its basic wage from $2.40 for a nine-hour day to $5 for an eight-hour work day. Many of Ford’s contemporary critics scorned his “Five Dollar Day.” Journalists and other auto makers predicted disaster for the industry. Henry Ford implemented the wage increase to head off labor unrest in the company and curtail his problems with worker turnover. The wage increase helped to derail efforts to start a union in his factory. The five-dollar day was not an act of altruism by the automaker. It was a calculated business decision. Most importantly for Ford, the wage increase enabled his workers to become customers and buy cars of their own. Ford declared, “One’s own employees ought to be one’s own best customers.” Despite the prognosticators of doom, Ford’s plan worked. Ford’s profits doubled in the two years after he raised the wages. In 1914 Ford sold more than 300,000 Model Ts, more than all other U.S. automakers combined. By 1920 that number had climbed to a million cars a year. Reflecting back on his decision Ford explained, “The payment of five dollars a day for an eight-hour day was one of the finest cost-cutting moves we ever made.” Perhaps those who today are lining up to predict doom and disaster if the minimum wage is raised might benefit from reading this page from labor history.

Tuesday Jan 04, 2022

January 4

Tuesday Jan 04, 2022

Tuesday Jan 04, 2022

Last year Chicago saw the end of what may have been the longest hotel strike in history. On Father’s Day 2013, 130 workers from the Congress Hotel on Michigan Avenue walked off the job. They were protesting a reduction in wages and the hotel’s hiring of minimum-wage subcontractors. For ten years the strikers, let by Unite Here, picketed the hotel. The hotel management remained unmoved. Unite Here quietly ended the strike. But that was not the longest strike in history-not by a long shot. Today in labor history, January 4,1961, barbers assistants in Copenhagen, Denmark ended their strike. They had first walked off the job in 1928—and the Guinness World Book of Records has declared the strike the longest in recorded history! Every strike, or a work-stoppage, has its own character. A strike might be as short as just a portion of a day. Or a strike might last for weeks, months, or years. Sometimes union members call strikes to last a specific amount of time—usually a few days. Other times union members vote for an open-ended strike, with the duration uncertain. The tactic of a strike is one of the most extreme measures a union can take. Usually, a strike means that all other efforts to gain a fair contract have been exhausted. Long strikes have become less common in recent years. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics there were only 15 major work stoppages in 2013. Of these two-thirds lasted three days or less.

Monday Jan 03, 2022

Sunday Jan 02, 2022

Saturday Jan 01, 2022

January 1

Saturday Jan 01, 2022

Saturday Jan 01, 2022

Today in labor history, January 1, 1863, is one of the most often misunderstood days in United States history. This was the day that Abraham Lincoln issued the “Emancipation Proclamation.” But did you know that Emancipation Proclamation did not actually free enslaved people in the U.S.?

Friday Dec 31, 2021

December 31 - Fighting for Safer Working Conditions

Friday Dec 31, 2021

Friday Dec 31, 2021

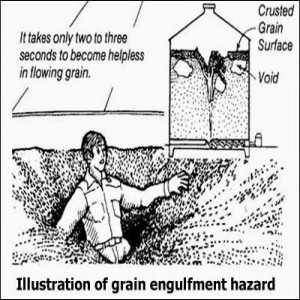

On this day in labor history, the year was 1987.

That was the day OSHA issued its final rule on Grain Handling Facilities.

This standard was established almost ten years after discussions and Congressional hearings began on the subject.

There had been a series of catastrophic explosions in the late 1970s, which dominated national attention.

A special task force was created by the U.S. Department of Agriculture to investigate grain elevator safety and explosions after 13 USDA inspectors were killed in 1977.

Five separate incidents involving grain elevator explosions killed 59 and injured another 49, just in December of that year alone.

The USDA task force issued a report with guidelines soon after the National Grain and Feed Association conducted its own research and guideline issuance.

By 1981, the Food and Allied Service Trades Department, AFL-CIO petitioned OSHA to promulgate a rule regulating the build-up of explosive dust in grain elevators.

When the final rule was issued, it focused on requirements for the control of fires, grain dust explosions, and hazards associated with entry into bins, silos, and tanks, as well as hazards associated with the release of hazardous energy from equipment.

The standard held employers responsible for developing emergency action and escape plans as well as worker safety training.

The standard also set rules for safe entry procedures.

When the standard came up for review in 1998, OSHA noted that for the previous forty years, there had been 600 explosions, 250 deaths and over 1000 injuries related to grain elevator explosions.

They also determined there had been a 70% decrease in fatalities from explosions and a 44% decrease in suffocations in the years after the final rule had been issued.

Thursday Dec 30, 2021

December 30 - The Day Mines Were Made Safer

Thursday Dec 30, 2021

Thursday Dec 30, 2021

On this day in labor history, the year was 1969.

That was the day President Richard Nixon signed the Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act into law.

At least three key events served as the impetus for the legislation.

Beginning in the mid 60s, miners began staging numerous health and safety walkouts across the Appalachian coalfields.

Their working conditions were despicable.

Then, in November 1968, 78 miners were killed in a methane and coal dust explosion at Consol Mine no. 9 in Farmington, West Virginia.

Miners were outraged when UMW leader Tony Boyle provided cover for the company’s murderous negligence.

Then, in January, thousands of miners rallied in West Virginia’s state capitol, along with the Black Lung Association and the Disabled Miners and Widows.

They demanded legislation controlling coal dust and compensating black lung victims.

When the hearings dragged on, 30,000 miners walked out in a wildcat the next month, in what is referred to as the 1969 Black Lung Strike.

By March, the number would increase to 40,000.

The state law passed March 12. Fears of a nationwide health and safety wildcat strike prompted Congress to craft and pass the federal Act.

According to historian Paul Nyden, “the West Virginia Black Lung strike was the longest political strike in modern U.S. labor history.”

The Act created the Mine Safety and Health Administration.

It mandated annual inspections and increased federal powers of enforcement.

The Coal Act also required monetary penalties for all violations, and established criminal penalties for knowing and willful violations.

The Act developed improved mandatory health and safety standards and provided compensation for miners disabled by Black Lung disease. Miners continue to fight for better conditions, enforcement and compensation today.