Episodes

Tuesday Feb 28, 2017

February 28 Fighting for Equal Pay

Tuesday Feb 28, 2017

Tuesday Feb 28, 2017

Today in Labor History, February 28, the year was

On this day in Labor History the year was 1942.

That was the day that Sue Cowan Williams filed a lawsuit for equal pay for black school teachers in Little Rock, Arkansas.

Eighty-six black teachers worked in the city’s segregated school system.

They were all members of the Little Rock Class Room Teachers Association.

In 1941 the teachers formed a Salary Adjustment Committee to look into pay discrimination.

They found there was a wide gap between black and white salaries.

The average white elementary school teacher made $526 a year, while black teachers earned only $321.

White high school teachers brought home $856, but black teachers made only $567.

Backed with this research, the committee presented a petition to the School Board demanding an end to the pay discrimination.

The board tabled the petition, and that summer passed another round of unequal pay raises.

The teachers then approached the NAACP and asked them to handle their case.

Thurgood Marshall agreed to take up the lawsuit.

Marshall would go on to become the first black US Supreme Court Justice.

Sue Cowan Williams, the head of the English Department at Dunbar High School was selected as the plaintiff for the case.

The teachers lost their lawsuit, and then won on appeal.

But Williams paid a price for her involvement.

The next year the school district did not renew her contract.

She was finally rehired to teach at Dunbar a decade later.

But first the School Superintendent called Williams to ask if she had “learned her lesson.”

It was a lesson that many workers have learned—that there is often a high personal cost for standing up for justice on the job.

Monday Feb 27, 2017

February 27 Women Standing Up by Sitting Down

Monday Feb 27, 2017

Monday Feb 27, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1937.

That was the day whistles blowing and the call to strike could be heard through the aisles of Woolworth in downtown Detroit.

108 saleswomen walked away from their workstations and cash registers.

The eight-day sit-down had begun.

The young women saw from the experience in Flint that sit-down strikes could win.

They evicted management, barricaded the doors and found 200 or so customers still inside the store, wanting to join them.

The strikers issued their demands: a 10 cent an hour raise, an eight-hour day, union recognition and a union hiring hall, free uniforms and laundering and more.

Kresge department stores immediately gave their workers a raise in order to prevent similar stoppages.

The striking women at Woolworth made themselves comfortable and the sit-down soon spread to a second store.

Leaders from Local 705 of the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees threatened a national strike if demands were not met.

Union cooks provided meals and union musicians provided entertainment. Hotel workers from across the city picketed in front of the store to show solidarity.

After seven days, Woolworth’s management caved and agreed to most of the strikers demands.

High turnover in the workforce would undo contract gains at area Woolworth stores soon after the sit-down.

But the victory electrified retail workers across the country.

The sit-down spread to retailers in St. Louis, New York, San Francisco, Minnesota and Washington.

In Three Strikes: Miners, Musicians, Salesgirls, and the Fighting Spirit of Labor’s Last Century, Dana Frank notes that, “over 60 years later, unions today in department stores all over the country owe their existence in part to the Woolworth strike.”

Sunday Feb 26, 2017

February 26 “The Battle at Bethlehem”

Sunday Feb 26, 2017

Sunday Feb 26, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1941.

That was the day “The Battle at Bethlehem” began. 14,000 workers at Bethlehem Steel’s Lackawanna Mill in Buffalo, N.Y., walked out on strike.

The Steel Workers Organizing Committee, or SWOC, had been fighting to organize Little Steel for years.

‘Little Steel’ was a general term that referred to the smaller mills like Republic, Inland, Bethlehem and Youngstown Sheet & Tube.

At Bethlehem, SWOC was still waiting on a decision from the U.S. Court of Appeals about the company union Bethlehem refused to give up, in defiance of the Wagner Act.

As a defense industry, Bethlehem had $1.5 billion worth of armament orders to fill.

And yet, they wouldn’t even pay the legal minimum wage mandated for government contracts.

Retired steel worker, Mitchell Scheffer recalled in a 1991 interview, "I went to work there in the late 1930s swinging a 20-pound sledgehammer to break iron billets," says the 81-year-old. "I got 40 cents an hour, six days a week, no vacations"

The last straw was when Bethlehem fired over 1000 workers.

Bethlehem claimed these particular workers damaged coke ovens when they engaged in a work stoppage.

Workers immediately formed solid picket lines at seven gates that stretched two miles.

They successfully beat back attempts by police to scab herd.

After 38 hours, Bethlehem quickly agreed to reinstate the 1000 workers.

They soon resumed talks regarding wage increases, grievance procedures and union recognition.

But a month later, Bethlehem decided to go back on their promises.

They started organizing elections for collective bargaining representatives through their company union.

The stage was set for the next big strike at Bethlehem in March that would finally win union recognition.

Saturday Feb 25, 2017

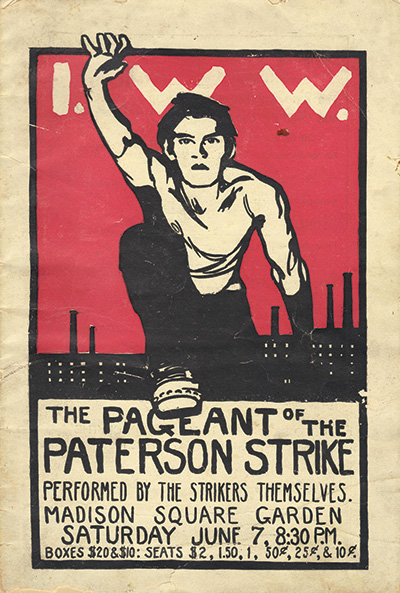

February 25 Paterson Silk Strike

Saturday Feb 25, 2017

Saturday Feb 25, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1913.

That was the day some 24,000 workers in Paterson, New Jersey walked out of 300 silk mills and dye houses to demand the eight hour day, better working conditions and a return to the two loom system.

Mill owners attempted to introduce a reduction of the workforce by doubling the number of looms workers ran, from two to four.

Descendants of strikers recalled a 55 hour workweek and children as young as nine working in the mills.

The strike started in late January at Doherty Mills and soon spread to become a general strike.

Leaders from the Industrial Workers of the World like Big Bill Haywood, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn and Carlo Tresca organized rallies, strike support and food pantries for the silk workers.

The police routinely attacked picket lines and as many as 1,850 workers were arrested during the course of the strike.

Socialists like John Reed put on a play at New York City’s Madison Square Garden that reenacted the strike to raise relief funds.

35,000 turned out to hear Upton Sinclair address the strikers.

Having stockpiled surplus product, manufacturers were able to outlast workers, who by July, were practically starving.

A main cause of the strike’s failure was the introduction of labor saving technology that served to reduce the need for highly skilled workers and drive down wages.

The strike may have failed in many of its demands but silk workers were able to beat back implementation of the four-loom system for almost a decade.

They would finally win the eight-hour day in 1919.

Importantly, the strike succeeded in uniting male and female workers across national and craft lines.

Friday Feb 24, 2017

February 24 Muller v. Oregon Decided

Friday Feb 24, 2017

Friday Feb 24, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1908.

That was the day the United States Supreme Court decided the case, Muller v. Oregon.

It was a landmark decision in the realm of protective labor legislation.

It restricted the workday to 10 hours for women.

Laundry owner, Curt Muller, required his female employees to work more than 10 hours a day, against Oregon labor laws.

The Supreme Court upheld his conviction and fine.

Protective labor legislation was a product of the reform social movements of the Progressive Era.

Reformers like Jane Addams worked to protect women from industrial dangers that bred physical and moral harm to women.

The decision drove a class-based wedge within the women’s movement that lasted for much of the 20th century.

Working class women generally supported protective labor legislation like Muller.

But Equal Rights Advocates like Alice Paul opposed it.

They argued that protective legislation like Muller rested on stereotypes regarding differences between men and women.

These differences often fueled anti-woman discrimination, state control and financial dependency.

As well, critics remarked the ruling set a precedent for women’s biology as child-bearers, as a basis for separate legislation.

Only later would working class critics note that the ruling did not cover domestics, agricultural workers, or white-collar workers.

The 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act would supplant some parts of Muller with its guarantees for workers of both sexes.

Many working class women later welcomed the passage of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act in 1965, which prohibited employment discrimination.

Some would concede the many flaws of protective labor legislation that held women back.

But women’s rights advocates would continue to debate protective legislation and the Equal Rights Amendment well into the 1970s.

Thursday Feb 23, 2017

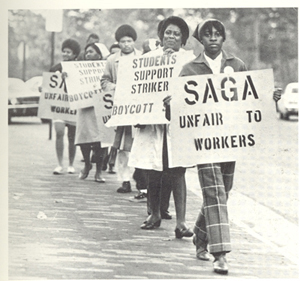

February 23 Low Wage Workers Say Enough

Thursday Feb 23, 2017

Thursday Feb 23, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1969.

That was the day black food workers went on strike at University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.

Their strike intersected many points central to the social upheaval of the period, including rights of public sector workers.

Besides extremely low wages, workers complained of racial abuse and discrimination on the job.

When the administration ignored their demands, the cafeteria workers sat down at the tables and refused to return to the kitchens.

Black women workers like Mary Smith and Elizabeth Brooks organized protests and rallies to build public support on and off campus.

As the strike wore on, many students rallied to their defense.

The Black Student Movement was the first campus group to support the cafeteria workers.

Noting the lag of desegregation on Southern campuses and in the South generally, black students added their own demands to those of the workers.

They included the expansion of black student aid programs and black studies programs.

Clashes escalated between students at Lenoir Hall a few weeks later when opposing white students attacked integrated groups of students sympathetic to the strike, forcing the closure of the cafeteria hall.

Governor Robert Scott ordered the National Guard on standby.

Finally, workers formed a union and won many of their demands.

This benefitted 5000 other state employees as well.

But a month later, the UNC administration betrayed them by contracting out food service.

Many were laid off or fired for union activity.

By the end of the year, the now AFSCME organized workforce struck again over many of the same issues.

When renewed student strike support was threatened, management quickly caved and the strike ended in victory.

Wednesday Feb 22, 2017

February 22 Labeling Teachers as Terrorists

Wednesday Feb 22, 2017

Wednesday Feb 22, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 2004.

That was the day Secretary of Education, Rod Paige stated he considered the National Education Association to be a terrorist organization.

He made the remarks during a meeting with governors who were visiting the White House.

His apology a few hours later was just as inflammatory.

There he expressed his frustration at the "obstructionist scare tactics the NEA’s Washington lobbyists have employed against No Child Left Behind’s historic reforms.”

Representing almost three million educators, the NEA had been fighting many aspects of the No Child Left Behind Act, passed by Congress in 2001.

The teachers’ unions had initially supported the measure.

But they came to realize that the act was designed to undermine public education in favor of charter, private and religious schools.

‘No Child Left Behind’ mandated regular, standardized testing of students.

It also threatened financial penalties and school closures.

Governors on board with the goals of the Act soon grew frustrated.

The Bush administration reneged on federal funding necessary for its implementation.

The union movement was outraged at Paige’s smear.

John Sweeney, then president of the A.F.L.-C.I.O., said, ''The Bush administration would like to label all those who disagree with it as terrorists in order to cover up its policies, which are harmful to working families, and to divert attention from its inability to create good jobs.''

By 2015, the ‘No Child Left Behind Act’ had received so much criticism from every corner, that the ‘Every Student Succeeds Act’ replaced it.

This Act retains Common Core standards but transfers school accountability to the states.

It is now pending review under President Trump’s regulatory freeze directive.

Tuesday Feb 21, 2017

February 21 The First Female Telegraph Operator

Tuesday Feb 21, 2017

Tuesday Feb 21, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1846.

That was the day Sarah Bagley became the first female telegraph operator.

She was hired at the office in Lowell, Massachusetts.

Sarah spent weeks studying the electrical theory behind the new technology and began her job in earnest.

She soon quit in protest after learning her pay was far less than her male counterparts.

Bagley was no stranger to labor struggles.

She was among the many Lowell textile workers who struck in 1842.

Bagley was one of the founders of the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association.

She fought for the 10-hour day and better working conditions in the mills.

Sarah also helped to found the labor paper, The Voice of Industry.

When the Reform Association demanded state investigations into working conditions at area mills, she stated, “Is anyone such a fool as to suppose that out of six thousand girls in Lowell, sixty would be there if they could help it? Whenever I raise the point that it is immoral to shut us up in a room twelve hours a day… I am told that we have come to the mills voluntarily and we can leave when we will. Voluntarily! … the whip which brings us to Lowell is necessity. We must have money; a father’s debts are to be paid, an aged mother to be supported, a brother’s ambition to be aided and so the factories are supplied. Is this to act from free will? Is this freedom? To my mind it is slavery.”

Bagley returned to Lowell’s Hamilton mills after she quit the telegraph office.

She briefly continued her activism until she married and moved to Brooklyn.

Monday Feb 20, 2017

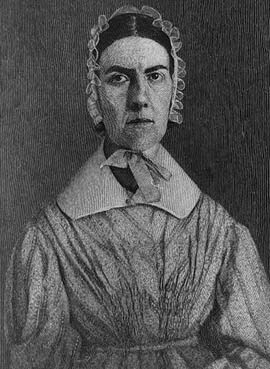

February 20 Angelina Grimke is Born

Monday Feb 20, 2017

Monday Feb 20, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1805.

That was the day abolitionist and women’s rights advocate Angelina Grimke was born.

Her parents were slaveholders and among the wealthiest in Charleston, South Carolina.

As a young woman, she denounced slavery and together with her sister, Sarah, moved north to Philadelphia to join the Quakers.

There she became a teacher but grew frustrated with how the Quakers approached abolitionism.

She quickly gravitated towards radical abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison and became active in the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society.

She became prominent in abolitionist circles in 1835 after Garrison published her letter condemning pro-slavery riots in Boston.

The next year, she published an open letter to Southern women demanding they condemn the institution of slavery.

Angelina and Sarah embarked on abolitionist speaking tours and the organizing of women’s anti-slavery societies.

Having grown up in the South, the Grimke sisters held an especial authority among Northern abolitionists.

They could testify to the severity and inhumanity of the slave system.

They did so in the book, American Slavery As It Is, written together with Angelina’s husband abolitionist Theodore Weld.

Controversy intensified against Angelina and her sister as their popularity grew.

Religious leaders and abolitionists alike bristled at the idea of women engaged in public speaking and political work.

Undeterred, the sisters defended their right to be on equal footing with men in the abolitionist movement.

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s sister, Catherine, a leading educator, was among those who decried women’s public activism.

Angelina responded that all humans are moral beings worthy of human rights, regardless of gender.

Her response served as an early contribution to the women’s rights movement in the 19th century.

Sunday Feb 19, 2017

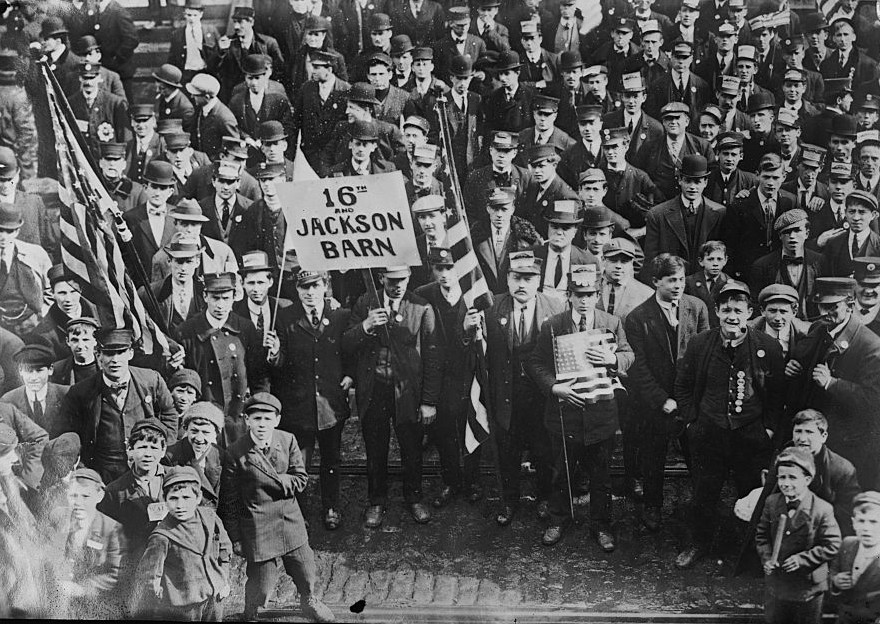

February 19 General Strike in Philadelphia

Sunday Feb 19, 2017

Sunday Feb 19, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1910.

That was the day streetcar workers in Philadelphia walked off the job just as garment workers were ending their victorious strike.

The walkout soon turned into a general strike.

The Amalgamated Association of Street and Electric Railway Employees Local 477 had been trying to negotiate fewer hours, higher wages and union recognition for almost a year.

Philadelphia Rapid Transit broke off negotiations in mid-February, fired 173 union members and imported scab replacements from New York City.

The Amalgamated called workers out. Strikers pulled apart buildings under construction and used the materials to block tracks and build strike shelters.

Many trolley cars were badly damaged when PRT attempted to resume service.

Scab drivers fared as badly as the trains they attempted to run.

The mayor called for citizens to serve police duty after strikers loaded dynamite onto tracks in Germantown.

The union offered up its members to preserve order but the Mayor refused.

Then the PRT brought in an additional 600 scabs and National Guardsmen to protect them.

Area workers were infuriated at this latest move, as were small businesses and religious groups.

On March 5, the Central Federated Union called a general strike.

More than 75,000 workers stayed off the job, to protest PRT’s anti-worker assaults.

Though the general strike was called off at the end of March, transit workers stayed out until April 19.

They won wage increases, rehiring of strikers and mediation for the initial 173 fired workers.

They could not secure exclusive union recognition.

But the strike solidified solidarity among area workers and demonstrated the capacity of labor to organize work actions across industrial lines.