Episodes

Saturday Jan 21, 2017

January 21 Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers Strike for Safety

Saturday Jan 21, 2017

Saturday Jan 21, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1973.

That was the day Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers struck Shell Oil over health and safety issues.

OCAW had been involved in lobbying for the passage of OSHA and other environmentally related Acts.

Their members worked in some of the most dangerous, most toxic industries in the country.

By 1972, they demanded contract language for health and safety committees on the job.

The oil companies countered with accusations that improved safety proved too expensive and that OCAW used the issue to assert union control over the production process.

The other oil companies eventually settled in OCAW’s favor.

But Shell would not budge.

And so, the OCAW called a strike at eight facilities and a boycott of all Shell products.

They also successfully enlisted the support of environmental organizations by stressing toxic chemical exposure and hazards faced by workers and the public alike.

Picket lines were solid and thousands honored the boycott.

Sales for Shell fell by 25%.

After four months, the strike fund was nearly drained.

Shell exploited internal divisions among members at a Texas plant and negotiated a separate settlement.

What health and safety language Shell agreed to, was non-binding.

The union was broke and the strike ended in compromise in early June.

Despite this, as historian Robert Gordon notes, OCAW was able to “gain strong health and safety language at all other oil companies for the first time, heightened public awareness of health hazards confronting millions of workers…and pressured OSHA into adopting stricter standards. Perhaps more importantly, the strike solidified the tentative labor-environmental alliance.”

Having merged with the United Steelworkers, the union continues to secure safe working conditions through contracts and alliances today.

Friday Jan 20, 2017

January 20 The Flint Women’s Emergency Brigades

Friday Jan 20, 2017

Friday Jan 20, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1937.

That was the day the Flint Women’s Emergency Brigades was founded.

Genora Johnson, a socialist, was a main leader of the Women’s Auxiliary Number 10 throughout the strike.

A different kind of auxiliary, it built the leadership skills of women through classes in labor history and public speaking.

It also set up a first-aid station and child-care center, raised strike funds and walked picket lines.

According to Janice Hassett, “the women moved beyond supporting the strike to participating in it.”

Fifty women signed up the next day.

By the end of the strike, over 300 women would join.

The women adopted an official uniform of red berets and red armbands.

They were armed with clubs to smash factory windows when police gassed sit-downers.

Their participation in the strike was heroic and their work continued after victory.

They sought to represent the interests of women autoworkers, who often found coworkers less than welcoming and experienced sexual harassment and occupational discrimination at the hands of supervision.

Many women autoworkers formed the core leadership of several chapters.

Historian Nancy Gabin notes that this was not always the appropriate arena for advocacy saying; “By encouraging women workers to participate in the auxiliaries, the UAW abdicated its responsibility to these workers.”

However, Johnson emphasized, “It was a radical change.... To give women a right to participate in discussions with their husbands, with other union members, with other women, to express their views... that was a radical change for those women at that time.”

Thursday Jan 19, 2017

January 19 A Snapshot in Misery

Thursday Jan 19, 2017

Thursday Jan 19, 2017

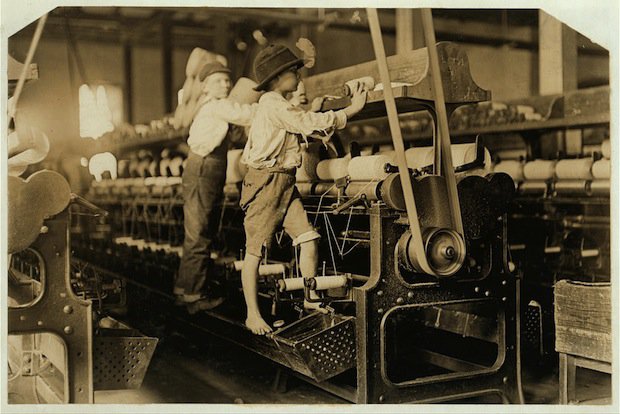

On this day in labor history, the year was 1909.

That was the day Lewis Hine photographed child workers standing on spinning frames to mend threads and replace empty bobbins at the Bibb Mill No.1 in Macon, GA.

It was just one example of the appalling use of children in industrial labor.

Hine built his career on photographic portraits of young miners and mill workers, child cotton pickers and factory workers.

In 1908, he was hired by the National Child Labor Committee to document child laborers across the country.

For the next fifteen years, Hine would contribute over 5000 photographs to the cause of ending child labor.

Photo historian Daile Kaplan described the ways in which Hines captured these images writing: “…Hine the gentleman actor and mimic assumed a variety of personas--including Bible salesman, postcard salesman, and industrial photographer making a record of factory machinery--to gain entrance to the workplace. When unable to deflect his confrontations with management, he simply waited outside the canneries, mines, factories, farms, and sweatshops with his fifty pounds of photographic equipment and photographed children as they entered and exited the workplace.”

NCLC investigators referenced the photographs in reports on particular industries and locations.

The NCLC used the photos to illustrate its own publications and succeeded in placing them in newspapers, progressive publications and exhibits.

One NCLC poster that featured Hine’s portraits read, “Making Human Junk: Shall Industry Be Allowed To Put This Cost On Society?”

By 1912, the NCLC persuaded Congress to create a United States Children’s Bureau.

The two organizations worked together to investigate abuses of child laborers.

Years of legislative and judicial battles followed, until finally in 1938 Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act.

Wednesday Jan 18, 2017

January 18 Supreme Court Again Decides Against Workers

Wednesday Jan 18, 2017

Wednesday Jan 18, 2017

On this day in labor history the year was 1909.

That was the day the United States Supreme Court decided the case of Moyers v. Peabody.

The case grew out of the Colorado Labor Wars, a series of back-to-back strikes in 1903 and 1904 in precious metals mines and ore mills.

The Colorado National Guard meted out violent assaults, arrests and deportations against strikers, often on orders from Governor James Peabody.

The state militia routinely rounded up strikers and union leaders, detained them for weeks in bullpens and ignored habeas corpus petitions.

Western Federation of Miners president, Charles Moyer arrived in Telluride during a strike to find these repressive conditions.

He signed a poster that read, “Is Colorado in America?”

The poster included an image listing the many violations of basic democratic rights on the American flag.

Moyer was arrested in March 1904 for desecration of the American flag on the poster.

He was detained on the grounds of military necessity, even after the courts ordered his release.

His case traveled through the state and federal courts until the Supreme Court ruled.

They held that “the governor and officers of a state National Guard, acting in good faith and under authority of law, may imprison without probable cause a citizen of the United States in a time of insurrection and deny that citizen the right of habeas corpus.”

The ruling radicalized the labor movement.

Many concluded there could be no justice through the court system.

A later case successfully challenged the ruling on the basis that claims of insurrection were subject to judicial review.

The ruling, however controversial, still stands and was invoked after 9/11 in the 2004 ruling Hamdi v Rumsfeld.

Tuesday Jan 17, 2017

January 17 Standing Against Wage Theft

Tuesday Jan 17, 2017

Tuesday Jan 17, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1898.

That was the day workers in the textile mills of New Bedford, MA walked out on strike.

They were organized along craft lines into five different unions.

Regardless of craft, mill owners inflicted a 10% wage cut, which would prove devastating, given whole families worked in the mills.

When the wage cut took effect, spinners effectively shut down twenty-two mills owned by nine companies.

Having formed an amalgamated strike committee, weavers, loom fixers, carders and slasher-tenders all stayed away in support.

Workers leaders like Samuel Gompers, Eugene V. Debs and Daniel De Leon of the Socialist Labor Party all visited the strikers to give encouragement and inspiration.

Debs alone acknowledged the role of women in the strike as workers and not just as wives, mothers, daughters or sisters.

Before the strike, there had already been discord over strike demands.

The weavers insisted on adding the fines issue.

They constituted 40% of mill workers and their job duties included correcting the mistakes of other trades.

Manufacturers routinely fined weavers for material deemed imperfect, yet still profited from selling their products.

The fines system wrought havoc on weaver families and they wanted it abolished.

The rest of the unions sympathized with their plight, but insisted the strike would fail unless they focused solely on the issue of wage cuts.

The weavers persisted and the demand stuck.

By April, the strike collapsed.

Workers went back with nothing gained.

But the strike proved that workers across craft lines could strike and support each other in an industrial manner.

It also proved that men and women workers could effectively organize a strike and picket together.

*The Photo is from the 1928 strike of Textile workers in New Bedford MA

Sunday Jan 15, 2017

January 16 The Radical Policy of Field Order 15

Sunday Jan 15, 2017

Sunday Jan 15, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1865.

That was the day General William T Sherman issued Field Order #15.

The order sought to redistribute 400,000 acres of land to freed blacks in 40-acre tracts.

The area stretched from Charleston, South Carolina to Jacksonville, Florida, from the Atlantic Ocean to thirty miles inland.

It also included many coastal islands as well as Georgia’s Sea Islands.

Coming on the heels of Sherman’s March to the Sea, the order was issued from Savannah, Georgia.

Four days earlier, Sherman had met there with twenty black ministers and Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton.

Sherman and Stanton asked the group a series of questions: How did they understand slavery?

And what did freedom mean to them?

When asked what the Freedmen wanted most, Garrison Frazier, the group’s spokesman, replied, “Land.”

And when asked whether they would prefer to live among whites or not, they replied no, “As the prejudice of whites would take years to overcome.”

The order provided for the immediate settlement of black refugees on confiscated land.

Land redistribution to former slaves was radical policy to break the economic power of the Confederacy, punish South Carolina for starting the war and begin to consolidate a new class of agricultural laborers.

The land titles were possessory however, and contingent upon the Freedman’s Bureau to award permanent titles.

President Andrew Johnson moved quickly in the wake of Lincoln’s assassination to overturn Field Order 15.

And within a year, it would be reversed and confiscated lands would be returned to newly pardoned Confederates and plantation owners.

The overturning of the Order and later, of Reconstruction, would lay the basis for a new type of slavery.

That of sharecropping, debt peonage and contract labor.

Sunday Jan 15, 2017

January 15 "We Want to Live, Not Just Exist"

Sunday Jan 15, 2017

Sunday Jan 15, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1946.

That was the day the United Electrical Workers joined the national post-war strike wave.

200,000 UE members walked off the job at General Electric, Westinghouse, and General Motors’ Electrical Division.

Across the country, reduction of hours and phony job reclassifications led to a 30% wage cut, while years of wartime grievances piled up.

All this led to the demand for $2 a day pay raises.

Many of these workers were young women on strike for the first time.

They had spent much of the war fighting piecework and gender based divisions of labor.

Reports from the picket lines showed overwhelming support among the strikers and from the general public.

Older male coworkers who built the UE joined young women strikers on the line.

At the GE Mazda Lamp Works in Youngstown, Ohio, steelworkers joined women strikers to bolster picket lines.

In Lynn, MA, signs of women picketers read, “We Want to Live, Not Just Exist,” and “Let the Pipes Freeze-They Don’t Care If We Freeze,” in response to maintenance crews allowed to pass.

In Bloomfield, N.J., six restaurants turned their establishments over to the strikers.

GE president Charles Wilson complained bitterly of the 12,000 or so picketers that blocked the gates of the GE Schenectady Plant.

Strikers across the country faced violent confrontations and beatings as police on horseback waded through crowds.

Philadelphia strikers retaliated by pouring marbles onto the street.

Workers at GE and Westinghouse would eventually settle for 18 cents an hour, less than what they had hoped but more than either company had been willing to give.

Management would remain in shock for years at the level of solidarity among strikers and the community.

Saturday Jan 14, 2017

January 14 The Rise of the Bellamyites

Saturday Jan 14, 2017

Saturday Jan 14, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1888

That was the day novelist, Edward Bellamy published his futuristic, utopian novel, Looking Backward, 2000-1887.

The protagonist, Julian West, wakes up in the year 2000, to find that industry has been nationalized and wealth, goods and services have been equitably distributed.

People work less, retire early and enjoy greater leisure.

Looking Backwards was so popular that by 1900 only Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Ben-Hur had sold more copies.

Bellamy’s utopia solved problems of capitalism through development of a socialistic society.

Bellamy denied he was a socialist and instead referred to his vision as Nationalist.

The novel sparked a political movement virtually overnight.

Bellamyites, as they were called, formed Nationalist Clubs across the country.

They attempted to organize a Peoples’ Party around these clubs, which soon dissolved into the Populist movement of the 1890s.

Looking Backwards was a response to the Gilded Age world of monopolies and trusts, depressions and often-violent class convulsions.

Bellamy was quick to indict the banks, the railroads and the corrupt political system that served them.

Sociologist Arthur Lipow argues in his book, Authoritarian Socialism in America: Edward Bellamy and the Nationalist Movement, that while Bellamy may have expressed anti-capitalist sentiments, his future is one in which there is no democratic public life or political process.

For Lipow, Bellamy’s particular collectivist view is militaristic and bureaucratic, and does away with representative bodies of any kind.

However, Socialist Party leader Eugene V. Debs credited his own political development in part, to reading Looking Backwards.

He noted that, regardless of whether Bellamy considered himself a socialist, his novel generated popularity and enthusiasm for socialist ideas, causes and politics.

Friday Jan 13, 2017

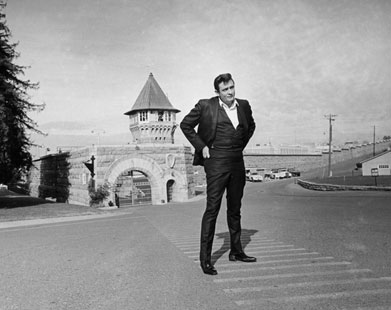

January 13 Johnny Cash Plays Folsom Prison

Friday Jan 13, 2017

Friday Jan 13, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1968.

That was the day Johnny Cash played Folsom Prison.

The Man in Black had played numerous free prison concerts before.

Country-music Legend Merle Haggard remembered seeing him perform at San Quentin a decade earlier.

Columbia Records recorded the two concerts at Folsom for release.

It was this recording that many credit with the revitalization of Cash’s career.

His daughter, Rosanne believes the 1968 appearance signified her father’s own personal liberation; “…that was the moment that he came into the light…when he embodied who he really was.”

Performing with The Tennessee Three, June Carter, Carl Perkins and The Statler Brothers, Cash hit the charts with Folsom Prison Blues, which sold more than three million copies at the time.

He also took the opportunity to advocate for prison reform and prisoner’s rights, providing congressional testimony on the subject in the early 1970s.

His brother told the BBC in an interview, "He identified with the prisoners because many of them had served their sentences and had been rehabilitated in some cases, but were still kept there the rest of their lives. He felt a great empathy with those people."

Cash might not have actually shot a man in Reno, but he always sided with the underdog.

His songs highlighted the workingman’s life, from the sharecroppers, coalminers and auto workers, to the railroaders, truckers and prison chain gangs.

Cash always gave an unromanticized view of hard living and hard labor, as well as interracial and class solidarity.

Thursday Jan 12, 2017

January 12 The Cost of Wartime Industrial Peace

Thursday Jan 12, 2017

Thursday Jan 12, 2017

On this day in labor history, the year was 1942.

That was the day President Franklin Roosevelt established the National War Labor Board under Executive Order 9017.

The Board was designed to mediate and settle disputes in the various defense industries.

Its purpose was to prevent any strikes or lockouts that would interfere with war production.

The War Labor Board consisted of twelve representatives: four each from industry, labor and the public.

It established procedures for dispute resolution and detailed the scope of grievances, arbitrations and award enforcement.

The Board had the authority to issue binding agreements and to recommend government seizure of plants involved in work stoppages.

It instituted the “Little Steel” Formula to allow for cost of living wage increases, in an effort to stem inflation.

In exchange for the no-strike pledge, it instituted “maintenance of membership” in unionized workplaces, which made union membership automatic for new hires and mandated employer collection of union dues.

During the war, it imposed tens of thousands of wage-dispute settlements and wage agreements.

In a 1942 case against General Motors, the Board mandated equal pay for equal work for women and minorities. ]

Those critical of the Board opposed the no-strike pledge and compulsory arbitration as clampdowns on Labor’s power and independence.

They argued it was stacked with open-shop advocates, enforced wage controls and freezes, and encumbered workers with endless red tape, run-arounds and delays in resolutions.

Labor historian Steve Fraser notes that after the 1942 elections, pro-business appointees made union organizing efforts throughout the South and in the retail and service sectors difficult.

It ceased to function at the end of 1935, though it set precedents for arbitration that are still in use today.